From admission to dissertation. Tips on making the PhD journey happy, productive and successful

How to Choose a PhD Research Topic in English Literature

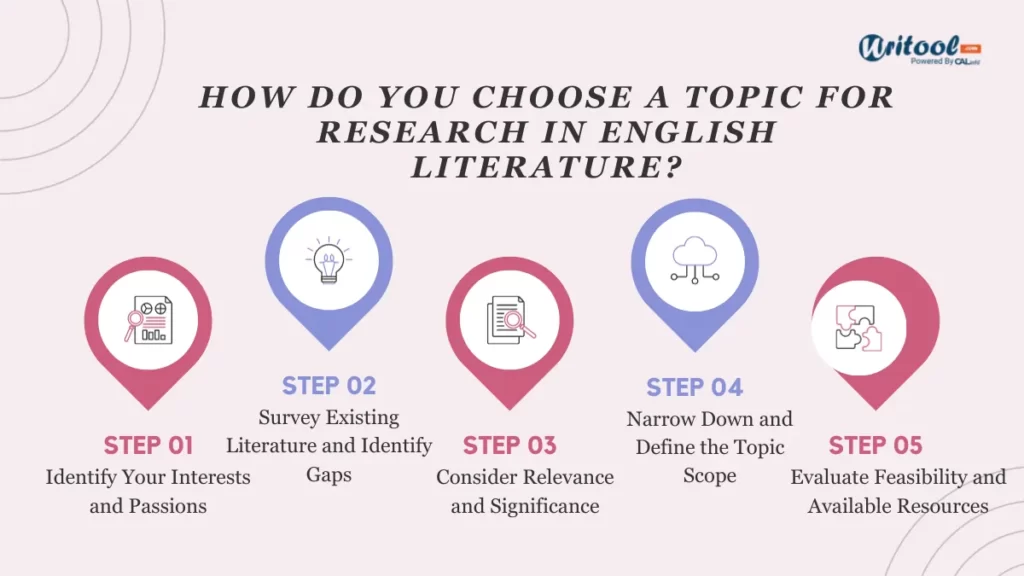

To pick a right topic for research in English Literature during PhD is something a huge task. There are many topics out there for a good research. Here are my tips on how to rightly choose a PhD research topic in English Literature

- Choose the right poet or author that interests your topic.

- Ask PhD. supervisor the relevance of the poet to research.

- Search for some areas of research taken in the past.

- Choose a new topic that was not researched in the past.

- Check if sufficient Primary Sources are available or not.

- Try to take help from professors around you.

- Buy some books that are relevant to English Literature.

- Read for some days about the research topic.

- Read more literary theories and apply them to your PhD topic.

The proven way to choose a research topic in English Literature is to ask your professor on what they have researched upon while they had been doing their Ph.D. After this, you have to search for new trending topics at the present time. If someone has got an award or Nobel prize, Take that person and it is always best. Every year there are awards given to the authors who contributed well to English Literature. Choose a topic from them.

First, choose the right author to research

You’re about to choose an author to research for your Ph.D. in English literature. This is important and so you should take your time doing. You want to ensure the author is someone who is interesting and intriguing for everyone in the literary academic world. The words of the author need to be words that will make you think, question and analyze.

Start off broadly, looking at a number of authors. Slowly narrow down your search. You need to connect to the author – how is his or her work significant, why does it appeal to you, will it appeal to academics, is there enough to write on, and is he or she relevant. Look at how much work he or she has written and made quite sure you can get your hands on the books.

Relevance is important. We live in a time where gender is a top priority, as is history, politics, art, feminism, sexism, the way stories are told and who tells them. Your Ph.D. is going to be based on this author. His or her words need to be relevant, perhaps controversial and significant. This author needs to be engaging and someone whose work you can engage with.

Learn more about the books of the author

As an academic, reading and research are the two most important thing you are going to do. You need to read as much as you possibly can, not just on the author of your choice, but all the books written by the author of your choice. Reading is something that you learn from but also something that stimulates you and gives you your own writing style.

The more you can learn about the author, the better you can come up with a research topic in English literature. Read as many of his or books as possible, but also, read books or articles that have been written about the author. After a while, you will start to feel like you know and understand the author. This is what you want. The more you read, the more knowledgeable you become, in every aspect.

If you cannot find the books – some may be obscure – spend time in libraries. Libraries are in fact very conducive to writing a Ph.D. – something about the bookshelves, space, the solitude and of course, the history. Remember, you want to find angles or information on the author that is new. Look online, look in libraries and don’t feel shy to ask your lecturers if they have books for you to borrow.

Learn more about the author’s personal life

You may already know that what an author writes about does not have to reflect his or her personal life. Which means when you are researching an author, you do not only want to learn about his or her written words? These words are important. But so are their personal words. Personal lives give you a good insight into the author too. If he or she had children, did they work alone, how did they die?

When we say personal words, we also mean personal life. Because the written word is different to the ‘living word’, an author can have many personas. Perhaps they write about sexuality in a very open way yet in real life, are deeply conservative. This makes for an interesting Ph.D. Knowing how the author lived out her personal life is very important.

You are going to have to delve into realms of information to learn about an author’s personal life. This is going to be interesting for you, and for your reader. In today’s world of fake news, you also need to be very careful. Double check your sources, always, to ensure you are getting and then choosing out the correct information. Read, and then read some more.

Read thoroughly all the novels for ten days

This may seem extreme to you, but we have already said that a successful Ph.D in English Literature is about reading and research. You’ve chosen your author and you’ve written out a list of his or her books. Now, you are going to curl up in a corner somewhere, or at your desk, and read. We’ve already said it but the more you read, the more you learn.

Spend the next ten days reading. This way you are immersing yourself in the author’s words, subjects, feelings, emotions, history, religion, characters, sexuality, gender and more. The more you read, the more you will start to understand your chosen author and to feel and think the way the author did or does. Remember, reading not only educates you, but it also inspires you.

Make notes as you read. Choose a pen or highlighter and highlight those passages that make you really think. Cross-reference paragraphs, characters, emotions or metaphors. Take note of anything you find important or astonishing or unusual or surprising. Go back to your notes. Your very Ph.D. may relate to your first few notes. Keep all your reading material too; one day you are going to need it. All Ph.D. students seem to buy new bookshelves!

Write down the summaries on your own

The best way to understand something, and to remember something, is to write. The more you write, the easier things will stick in your head. Read a book, or a few chapters, and then write your own summaries. Chances are your time is limited, which is why summaries are good. Also, when you write a summary, things start becoming clearer and you may have an epiphany.

If the book you are reading has 15 chapters, perhaps summarize after every chapter. This is a personal choice – and of course, it depends on the books – but more summaries are better than less. Summarize in your own words and you will find that through summaries, you find your own style too. Cross-reference your summaries to the books you are reading.

When we say write, you may enjoy writing and you may enjoy typing. This is personal. Academics can generally be seen in front of their computers, hammering away at their keyboards. Type if you like, but sometimes writing with a pen and paper can actually get your creative juices flowing in a different way. Writing makes you think and gives you the ability to see things in a fresh way too. Always write, as much as you can.

Take a course on literary theories

There are many online literary theory courses that you can choose and we would suggest you sign up for one. The literary theory may seem academic and overwhelming but once you understand it, you’re on your way to writing a successful and highly revered Ph.D. Take a look and see how many prestigious universities offer courses on literary theory. That way you will see how important it is to do one.

A literary theory course will change the way you think about language, literature, society, and identity. A course will help you hone your critical reading skills and to understand theoretical terms such as postcolonialism, deconstruction, and Marxist criticism. A literary theory course will arm you with all the skills that you will need to dissect, criticize, analyze and understand your author, subject or topic you are researching.

There are many literary theory courses and you need to find one that will help you with your subject. A literary theory course will help you understand how you should approach literature, criticism verse theory, structure, analysis, and psycho-analysis of the subject and the author. You can choose to do one literary theory course and do it in your own time. There are many online courses; do one for a successful Ph.D.

Learn to relate those theories to each other

You’re writing a Ph.D. which is a huge step. You are going to bring in various literary theories which means not only do you need to understand the various literary theories, but you need to know how they all relate to one another. For a Ph.D. to be successful, you need to discuss, analyze, criticize and be open for debate. You also need to be open to criticism.

Take a look at the various literary theories. There are traditional literary theories and also formalism and new criticism. There are Marxism and critical theory and then there’s structuralism and post-structuralism. You are likely comfortable with some theories, and others not so much. Remember, fellow academics are going to question your theories and criticize you. Criticism is not always bad. It is academic criticism and it is there for a reason. Your research needs to be complete.

Again, a literary theory course can help you. Depending on your subject and author of choice, depends on which theories you will need to bring in. There are others – including new historicity and cultural materialism, ethnic studies and post-colonialism criticism. You need to relate them to one another. A course may help you to pick a good topic for PhD English literature.

Now think about how the author followed theories in novels

It’s important to note that in the academic world there are often many complex perspectives regarding literary theories. You need to read about your chosen author and have a look at how he or she followed literary theories in their books. Was there consistency? Was there a specific literary theory that was followed?

Sometimes the theories are simple and easy to follow. Sometimes there is a single theory or theme in a book. Sometimes theories are mixed, or many sides are given. You need to be able to read, review, analyze and understand the theories your author chose to follow. And your research needs to be so good, that fellow academics can analyze too and have brainwave moments from your writing.

Reading needs to be engaging, no matter the kind of reading. It also needs to make you think. Reading should stimulate. Sometimes, more than one theory is applied so that there are conflicting views, ideas, debate, and discussion. Take a look carefully at the author you are researching, their books, and the ideas that are put forward. Do they follow the theories you have been learning about? If so, which one or which ones. Do you have any theories of your own?

Choose one theory that pins your interest

You may find some literary theories more exciting than others. Perhaps post-colonialism is your thing, or Marxist criticism excites you. The trick is not to get too tied down to one theory, too soon. Read, read again, make notes, summarize and review. And look at various literary theories. You are going to find that some theories absolutely fascinate you and others you find irrelevant. Make notes and slowly you will be lead towards the theories that are right for you.

The more you read and make notes, the more one particular theory is going to leap out at you. It may be a slow process and in fact, the slower the better. This means your thinking is going to be clearer, and more critical. Once you find yourself honing in on a certain theory, you will find your direction.

Let’s say poststructuralism has caught your interest. You will now start thinking in a different light. You will find yourself coming up with your own theories, perhaps relating theories together, perhaps finding clarity in just the one. Make notes – you may not use them all, but you will find them useful when you start tying everything together. And always, always, theorize.

Jot down what others are researching

If you have not yet decided on your topic, make sure you know what other students are researching, or thinking of researching. You do not want to suddenly find out you are doing the same thing. And you do not want to waste your time. Jot down other people’s topics. Jot down any ideas you have and at some point, you will find it all comes together. Wake up and make notes. Sit with fellow researchers and make notes.

The thing about choosing a PhD research topic in English literature is that you constantly need to listen, read, listen to some more, research and keep reading. You also need to open yourself up to the conversation, with other researchers, Ph.D. students, and lecturers. Talk to others, even if your literary topics are different. Or even to make sure that they are different.

The academic world is constantly bouncing ideas off one another. It’s important to talk about your ideas, to get feedback on your ideas, and to listen to other people’s ideas. Keep a notebook with you at all times and jot down what and how other people are doing their research. You are not going to copy anyone, but you are going to find inspiration and you are going to inspire others.

Don’t take already beaten topics

You need to put effort into finding the right PhD topic. This can take time and be agonizing. It may seem like each topic you are choosing has already been taken. Take your time and find a topic that appeals to you, will challenge you and will exit you. Find a topic where you can give new and exciting information too.

Choosing a topic for your PhD in English literature may depend on the literature available, how much time it is going to take you, and also, it the topic worthy of research and investigation. You are going to have to immerse yourself totally in all the literature available on the topic – choose wisely.

Only choose a topic already done if you are going to look at new angles and find different analyses to the ones out there already. Only choose a topic that you are pretty sure will become clear to you, as you research, and therefore clear to others too. You can choose a topic that is interesting to you, and been done before, as long as you have a new and exciting way from which to write.

Be creative and choose at least 5 topics randomly

Most students will look at up to 5 topics before making a decision. It’s quite normal to pick a topic, change your mind, pick another one, do some research, put it away, look at a third topic, and so on. This is a good process. You need to be proactive in your decision which means you need to spend time thinking of what you are going to write, and how you are going to write it.

The reason you choose at least 5 research topics in English literature is that you can really find that topic that excites and challenges you. Look at why you would study the topic and what your research would mean to you, and to others. Take your topics to fellow researchers or academics. Ask them for advice. Listen to what people have to say about your topic choices.

You may choose the first topic and have your heart set on it. Perhaps you find little information on it, or even worse, you find too much. The topic may have been over-researched. It is time to move on to your next topic until you settle on the one that is right for you. Don’t be hasty in making a choice.

Sit with a literature expert for review of topics

Once you have your list of possible topics for your Ph.D., ask a literature expert to spend some time with you. This could be a professor, lecturer, fellow researcher, or author. Put forward your ideas and ensure you have the correct information on your ideas. Ask for feedback. When you ask for feedback, listen without getting defensive. You have asked for a review of your topics. Listen to the feedback.

A literature expert can be someone you know but it doesn’t have to be. If you know about a specialist in your area of interest, ask for a meeting. And remember, you can also approach a professional organization and ask to chat. Fellow academics are generally happy to help. You can find fellow academics at your university but you are also free to chat with academics at other learning institutions.

Finally, use the Internet. You can find a variety of sources online that will answer any questions you may have regarding your proposed topic. You will be able to get ideas online about your proposed topics, and if they can work, if they have been done, if you are on the right path, and if there is interest.

Consult 5 English teachers and show the topics

You are choosing a PhD research topic in English literature and so it makes sense for you to discuss your various topics with an English teacher. You are taking to the very people who are going to have an interest in your ideas and you will find good English teachers are eager to talk to you. You will find teachers at your own place of learning, but you can also ask for meetings with teachers you don’t know but are expert in their field.

Tell them about your ideas. Ask them for feedback, what they think and if they would advise you to do the proposed topic. Ask if they think your topic has good potential and if it could become a dissertation. Ask them what they know about the topic and if they feel it would be significant. Listen carefully to the advice you are given.

You want your topic to uncover new information. You might think you have new information, but experienced English teachers may know differently. Chat with them, listen to them more important, and ask for their honest opinions. The academic world is an inclusive one and experts are going, to be honest with you. Listen to them.

Get the topic automatically suggested by your teachers

Choosing a Ph.D. topic in English literature is no easy task. Your research needs to be significant and helpful to future researchers. It has to be groundbreaking. It has to shed light on topics, or at least offer controversial opinions. It can be really hard to choose a topic, for these reasons. You may find that some of your teachers actually give out topics and this is an easy way to make a choice.

You can go for the topic that is automatically suggested by your teachers. This way you know that the topic is one that is significant and has not been over-researched or over analyzed. Chat with your teacher and ask why they are suggesting the topic. Get their advice.

When you choose a topic for your research, you want to get feedback from people who are ‘in the know.’ Don’t go with the first topic that comes along. Go with a topic that excites you and that you know will be hard work but interesting, creative and challenging too. Go with a topic that is going to have the academic world thinking and questioning, in a good way!

Do not reveal your topic to your friends before joining your PhD

You may think this is not something that should be up for debate but the truth is the academic world is a competitive one. If your idea is fantastic and food for thought and we hope it is, you don’t want a fellow student to follow your idea. Rather keep your research topic to yourself until you join your PhD. You don’t want your idea stolen, but you also don’t want to lose confidence in your idea, especially if you are convinced by it.

The other reason not to reveal your topic in advance is in case of friends brush off your idea. You may think your topic is worthy but somebody may take away your confidence. As long as you have done your research in advance and you feel strongly about your topic, keep it. Always listen to advice given by academics, but be a little more guarded with your friends. Do initially only.

Confidence is necessary when doing a Ph.D. You can drive yourself literally made when you question and the second question what you are doing. Don’t let friends or academics second guess you, unless you are asking their opinions. Otherwise, as long as you feel sure, keep going.

Attend various interviews taking the topic

This is a good tip for you when you are deciding about your research topic, but also once you have chosen your research topic. Universities are always having special interest lectures, interviews, workshops and more, and you will find all of these on your topic of interest. When we say interview, we mean an interview, a meeting, and a lecture.

Attend as many interviews as you can. This means you should try and go to all public lecturers or book readings or similar when you have chosen your topic. And if you are still choosing your topic, ask as many experts on the subject as possible to interview and talk to you. Remember; interview a wide range of people before settling on a topic. People are interesting and have interesting ideas – one person will give you something nobody else will have thought of.

One on one interviews or meetings can be the most beneficial thing. You, as the researcher, need to do a lot of listening. An interviewer will guide you in every single way and make you think. If an interviewer can make you think, imagine how one day you are going to make your readers think.

Try to buy novels

Have you ever seen an academic’s bookshelves? They are always jam-packed, floor to ceiling, with books. And academics have many bookshelves, not just one. Your research topic is going to be with you for a long time. It’s your Ph.D., you are going to read, research, write and defend. It’s yours and will be forever.

Buy all the novels and books you need. You are the expert on your subject, the expert on your topic. You need to read everything you can lay your hands on. And print is so much better than online. Take the books with you to bed, to the bath, to your coffee shop. Do more reading

It’s also an excellent idea to make a note of all the books you read. You will have a Ph.D. English literature file. Have an index and one of the chapters should include all the books by the author, and all the books you have read on the author. Summarize and make notes on the books. Make notes in the book. Read the book a second time if it really appeals to you.

Do not read novels on the computer

This is a contentious issue because academia is changing. There are two schools of thought – read novels in print or read novels on the computer. Don’t do both. The truth is you can do whatever works for you. If you prefer to read online, it is better than not reading at all.

The reason academia says ‘do not read novels on the computer’ is that they feel you may not retain as much. When you read in print you can make notes easily, highlight certain sentences or chapters, dog ear pages so you remember what to go back to, and also, read at any time.

Books are fantastic, especially in print. You always have them, you don’t have to go online to find them, they are real treasures and should be treated as such. And to have a whole range of novels or books on the subject of your thesis is something incredibly special.

Use time properly with some interest

It is very easy, especially in this world with the internet, to be distracted. When you are writing a Ph.D. the one thing you cannot afford is a distraction. You need to use your time properly and be incredibly disciplined. Many academics say when they write a Ph.D., they eat, drink and sleep it.

Let’s get back to discipline. Your thesis is going to take you a long time. When you undertake your research topic, think about the time frame that you have. You will need to manage your time well. You need to be well disciplined in giving yourself time to collect data and go through it.

Everyone needs to take a break sometimes. Do things that you enjoy in your free time. But when you are working on your Ph.D. work. Use your time smartly and always be reading, researching or writing. Do this and you will not have any last minute chaos in meeting your deadline.

Make a point to take short notes of ideas

The one thing you always need to have in your bag is a pen and pencil. Otherwise, have a mobile device where you can take notes. Ideas come to people at the strangest of times – when you’re taking a walk, sipping coffee, waiting for a friend on the corner. Always write them down.

Likewise, when you attend an interview or a lecture, have your pen and paper handy. Make notes so that you can refer to them and read them. Once you have got home, take your notebook and transfer anything relevant to your PhD folder.

Be aware of the interview or lecture, or meeting that you are in. It may come across as rude if you scribble down every little thing. Be discerning with your notes. Yes, write things down, definitely. But don’t write down an entire lecture. Listen, jot down short notes, and always – go over everything afterward.

Do some literary survey what others are interested

Before you choose your literary Ph.D. topic, do a lot of research. Your idea may be an extraordinary one, but what if nobody has any interest in reading it? You want to choose a topic that is interesting and excited and where the academic world will be talking about it.

Ask your lecturers what they think of your topic. Make notes and surveys. You could choose five topics – as suggested earlier – and run a literary survey. Ask lecturers, fellow academics and other students what they think of your topics. Put it in a survey form and see which topic comes out tops.

Look carefully at the results of your survey. If everyone is choosing one topic for a reason, they are probably right. It does not mean they are definitely right though. You can take your survey one step further and find out why they find that particular topic interesting. Then make a decision based on how you feel.

Do not take foolish and irrelevant topics

This is an obvious one, isn’t it? Nobody is going to read a PhD, or take it seriously when your top is foolish or irrelevant. We are living in a world where relevance is everything. Whether it does to with gender, feminism, sexism, history, climate change, politics or art – you must be relevant.

Remember, a PhD is something that everyone in the academic world takes seriously. Your research is going to be read by your peers and by peers who you hold in high esteem. You want them to read your work and be wowed by your work. If you are foolish, you lose your chance of being held in high esteem too.

You are going to be spending a long time on your PhD, maybe a year and maybe more. You also want to be interested in what you are doing and not find it a chore. Your research is important, not just for others but for you too. Take the whole thing seriously. PhD studies are serious – you need to be serious too.

Do lots of reading about other areas

You need to read as much as possible when you are writing a PhD. To be honest, you need to read as much as possible at all times. When you read other work, ideas come to you. You learn about style and content by reading. Read anything you can get your hands on. You are going to be writing your PhD. A good writer reads a lot, it is the only way they become a good writer.

When we say you should do a lot of reading, it does not mean you have to only read about matters connected to your particular research. You should read everything you can. Read academic papers, read transcribed interviews, read the newspaper, read novels and read magazines. The more you read, the better you write. Any writer will tell you that.

As a researcher, books are going to become the most important thing in your life. All books are going to become important to you. Keep a book in your bag. Read when you’re on the bus, on the train and at home in front of the television. Reading gets our own creative juices flowing, whether academic, fiction or non-fiction. Reading makes you think.

Keep all the collected notes and reading in hand

When you write a PhD you are going to have a ton of material that you need to go through. The first thing you need to do, even before you have chosen a topic, is to open up a PhD file. Get yourself a good one, it’s going to be with you for a long time. Make different sections.

Your collected notes are going to be the most important part of your Ph.D.; you are going to refer to them for a very long time. Make sure you have your notes in one section and as you can, cross-references them to your summaries or to chapters or books you are reading. Always go over your notes. You will suddenly read something and go ‘oh that makes sense.’

The same goes with all your reading. Keep your reading close by. Wake up in the morning, read. When you go to bed at night, read. The more reading you do, the better. Make notes of all the books you have, and of all the books you still plan to get. Tick them off as you read them. And mostly, always have a copy of your PhD notes and research as you go along. You do not want to lose it.

Popular posts that others are reading now::

- How many words per page in apa style format

- How to Finish PhD Quickly

- 19 Simple steps to Write a Research Paper

- Top 20 Scopus Indexed Journals in ELT 2021 List (English Language Teaching)

- Scopus Indexed Journals in English Literature

Syam Prasad Reddy T

Hello, My name is Syam, Asst. Professor of English and Mentor for Ph.D. students worldwide. I have worked years to give you these amazing tips to complete your Ph.D. successfully. Having put a lot of efforts means to make your Ph.D. journey easier. Thank you for visiting my Ph.D. blog.

You May Also Like

Top 29 Benefits and Advantages of doing PhD in Australia

What is the Eligibility for PhD in English

Age Limit For PhD in New Zealand

- How to Choose a PhD Research Topic

- Finding a PhD

Introduction

Whilst there are plenty of resources available to help prospective PhD students find doctoral programmes, deciding on a research topic is a process students often find more difficult.

Some advertised PhD programmes have predefined titles, so the exact topic is decided already. Generally, these programmes exist mainly in STEM, though other fields also have them. Funded projects are more likely to have defined titles, and structured aims and objectives.

Self funded projects, and those in fields such as arts and humanities, are less likely to have defined titles. The flexibility of topic selection means more scope exists for applicants to propose research ideas and suit the topic of research to their interests.

A middle ground also exists where Universities advertise funded PhD programmes in subjects without a defined scope, for example: “PhD Studentship in Biomechanics”. The applicant can then liaise with the project supervisor to choose a particular title such as “A study of fatigue and impact resistance of biodegradable knee implants”.

If a predefined programme is not right for you, then you need to propose your own research topic. There are several factors to consider when choosing a good research topic, which will be outlined in this article.

How to Choose a Research Topic

Our first piece of advice is to PhD candidates is to stop thinking about ‘finding’ a research topic, as it is unlikely that you will. Instead, think about developing a research topic (from research and conversations with advisors).

Consider several ideas and critically appraise them:

- You must be able to explain to others why your chosen topic is worth studying.

- You must be genuinely interested in the subject area.

- You must be competent and equipped to answer the research question.

- You must set achievable and measurable aims and objectives.

- You need to be able to achieve your objectives within a given timeframe.

- Your research question must be original and contribute to the field of study.

We have outlined the key considerations you should use when developing possible topics. We explore these below:

Focus on your interests and career aspirations

It is important to choose a topic of research that you are genuinely interested in. The decision you make will shape the rest of your career. Remember, a full-time programme lasts 3-4 years, and there will be unforeseen challenges during this time. If you are not passionate about the study, you will struggle to find motivation during these difficult periods.

You should also look to your academic and professional background. If there are any modules you undertook as part of your Undergraduate/Master degree that you particularly enjoyed or excelled in? These could form part of your PhD research topic. Similarly, if you have professional work experience, this could lead to you asking questions which can only be answered through research.

When deciding on a PhD research topic you should always consider your long-term career aspirations. For example, as a physicist, if you wish to become an astrophysicist, a research project studying black holes would be more relevant to you than a research project studying nuclear fission.

Read dissertations and published journals

Reading dissertations and published journals is a great way to identify potential PhD topics. When reviewing existing research ask yourself:

- What has been done and what do existing results show?

- What did previous projects involve (e.g. lab-work or fieldwork)?

- How often are papers published in the field?

- Are your research ideas original?

- Is there value in your research question?

- Could I expand on or put my own spin on this research?

Reading dissertations will also give you an insight into the practical aspects of doctoral study, such as what methodology the author used, how much data analysis was required and how was information presented.

You can also think of this process as a miniature literature review . You are searching for gaps in knowledge and developing a PhD project to address them. Focus on recent publications (e.g. in the last five years). In particular, the literature review of recent publications will give an excellent summary of the state of existing knowledge, and what research questions remain unanswered.

If you have the opportunity to attend an academic conference, go for it! This is often an excellent way to find out current theories in the industry and the research direction. This knowledge could reveal a possible research idea or topic for further study.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Discuss research topic ideas with a PhD supervisor

Discuss your research topic ideas with a supervisor. This could be your current undergraduate/masters supervisor, or potential supervisors of advertised PhD programmes at different institutions. Come to these meetings prepared with initial PhD topic ideas, and your findings from reading published journals. PhD supervisors will be more receptive to your ideas if you can demonstrate you have thought about them and are committed to your research.

You should discuss your research interests, what you have found through reading publications, and what you are proposing to research. Supervisors who have expertise in your chosen field will have insight into the gaps in knowledge that exist, what is being done to address them, and if there is any overlap between your proposed research ideas and ongoing research projects.

Talking to an expert in the field can shape your research topic to something more tangible, which has clear aims and objectives. It can also find potential shortfalls of your PhD ideas.

It is important to remember, however, that although it is good to develop your research topic based on feedback, you should not let the supervisor decide a topic for you. An interesting topic for a supervisor may not be interesting to you, and a supervisor is more likely to advise on a topic title which lends itself to a career in academia.

Another tip is to talk to a PhD student or researcher who is involved in a similar research project. Alternatively, you can usually find a relevant research group within your University to talk to. They can explain in more detail their experiences and suggest what your PhD programme could involve with respect to daily routines and challenges.

Look at advertised PhD Programmes

Use our Search tool , or look on University PhD listing pages to identify advertised PhD programmes for ideas.

- What kind of PhD research topics are available?

- Are these similar to your ideas?

- Are you interested in any of these topics?

- What do these programmes entail?

The popularity of similar PhD programmes to your proposed topic is a good indicator that universities see value in the research area. The final bullet point is perhaps the most valuable takeaway from looking at advertised listings. Review what similar programmes involve, and whether this is something you would like to do. If so, a similar research topic would allow you to do this.

Writing a Research Proposal

As part of the PhD application process , you may be asked to summarise your proposed research topic in a research proposal. This is a document which summarises your intended research and will include the title of your proposed project, an Abstract, Background and Rationale, Research Aims and Objectives, Research Methodology, Timetable, and a Bibliography. If you are required to submit this document then read our guidance on how to write a research proposal for your PhD application.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Navigating Your PhD Topic Choice

Embarking on an impactful research career, starting with your thesis.

We’ve compiled this guide to share the tools and frameworks we think will be most helpful to you if you’re searching for a meaningful thesis topic for your PhD.

About this guide

If you’re applying for a PhD, this guide can provide comprehensive assistance throughout your journey towards finding the best possible PhD for you. In the first part we focus on how you can decide whether to pursue a PhD, identify the values you want to guide your research and start generating research ideas. In the second half we will introduce a framework you can use to narrow your ideas down to a specific research question and ultimately create a PhD proposal. Finally, we will help you with finding the best possible supportive environment for your project and identifying the next steps of your PhD journey.

If you are not yet very familiar with core concepts like career capital and the ITN framework , we recommend reading the linked articles. We also recommend you read this article to understand why systematic approaches to career decisions are probably more useful than popular advice like “follow your passion”, and why helping others with your career will help you experience your job as more meaningful.

How to use this guide

We recommend completing this guide over multiple sittings, e.g. working through one section per week. However, please adjust the pace to suit your circumstances. We think you will get the most out of this guide if you start from the beginning, but you might want to skip some sections if you’ve already thought deeply about the content.

After reading the articles linked in each step, take some time (5-10 minutes) to answer the prompts we list, or to complete the exercises we recommend. We find that writing your thoughts down on paper is a step that people often want to skip, but it can help tremendously in getting clarity for yourself.

Is a PhD the right next step for you?

Lots of people “stumble” into PhDs. For example, they might see it as a default step in completing their education, or they might have been offered to continue with their previous supervisor. Before committing to a PhD programme, it is good to consider a broad range of alternatives in order to ensure that a PhD is the best path for you at this stage. Make sure you have done enough reflection and updated your plans based on your experiences thus far, instead of going down the “default” academic path.

We also recommend that you take some time to browse through these short descriptions of core concepts , particularly ‘Expected Value’, ‘Opportunity Cost’ and ‘Leverage’. Perhaps note down a few takeaways that apply to your decision.

Reflection prompts

If you’re unsure whether a PhD is right for you, here are some prompts to consider.

- Where do you envision yourself a few years after completing a PhD?

- How does a PhD align with your long-term goals and aspirations?

- Are you genuinely interested and intrinsically motivated by the subject area you intend to pursue with your PhD?

- Have you carefully assessed whether obtaining a PhD is a necessary requirement for your desired career path?

- Are there alternative routes or professional qualifications that may lead you to your desired destination more efficiently, e.g. in less time/ with a better salary?

- Have you talked to people who completed or are currently pursuing the kind of PhD you are considering?

Exercise: exploring career paths

One helpful activity to undertake could be to search for job opportunities that you find exciting. To start, do a job search (2-5 hours) and list the five most attractive options you can find. Now, check which job requirements you’re currently lacking. Do you need a PhD to get the role? Would you get there faster or be better prepared by taking a different route?

Here are some more articles if you are interested in the question ‘Who should do a PhD?’:

- Survival Guide to a PhD – Andrej Karpathy

- Why I’m doing a PhD – Jess Whittlestone

- Pro and Cons of Applying for a PhD – Robert Wiblin

Reflect on your values and moral beliefs

Understanding your values and moral beliefs is an ongoing endeavour and you don’t need to have it figured out before choosing your topic. However, we do encourage reflection on this, as doing so might significantly shift your motivation to work on some problems over others. If that happens, the earlier you make this shift the better. What do we mean when we say doing good ? Most people agree that they want to “do good” with their lives. However, it is worth reflecting on what this actually means to you. We recommend reading the article linked above to learn more about some concepts we think are particularly relevant when reflecting on this question, such as impartiality, the moral circle, and uncertainty. This will help you to get a better understanding of what sort of thesis topics would align with your values and what kind of problems you want to contribute to solving with your research.

- How much do you value animal lives vs human lives ?

- How important do you think is it to reduce existential risks for humanity?

- How much do you value future generations ? How do you feel about improving existing lives vs lives that exist in the future?

This flowchart from the Global Priorities Project can help you navigate through this cause prioritisation process.

Here are two further resources that could help you with this reflection:

How to compare global problems for yourself – 80,000 Hours

World’s Biggest Problems Quiz | ClearerThinking.org

Getting inspired

Now it’s time to get inspired! You can read more about how research can change the world , and how academic research can be highly impactful . Finally, have a look at our thesis topic profiles for inspiration or, if you have no time constraints, sign up to our Topic Discovery Digest to receive biweekly inspirational emails. These emails cover a range of particularly impactful research areas, along with example research questions that are recommended by our experts and relevant to many different disciplines of study. We recommend you read the 3-5 profiles that interest you the most in depth.

- Which of the topic profiles that sparked your interest are new to you? How could you quickly get a better understanding of what it is like to work on these topics?

- How would disregarding your current skill set change your top choices? Would you consider taking some time out to “upskill” to switch to a new area of research, if possible?

- What are the uncertainties that, if you could find an answer to them, would help you decide between your top choices?

See here if you want to learn more about how we go about writing our thesis topic profiles and why we prioritise these topics.

Side note: Because we try to feature problems that are particularly important, tractable, and neglected, you might see some problems listed on our site that it’s uncommon to see described as global problems, while others are not featured. As an example, in our “human health and wellbeing” category, we list anti-aging research but not cancer research. We think research on widely recognised problems such as cancer is highly important. However, because so many more researchers are already working on these problems, we think that – all else equal – you will probably have a bigger impact working on problems that are relatively neglected.

Generating ideas

After reading a few of our topic profiles , we recommend that you start a brainstorming document as an ongoing way of collecting research questions you’re interested in. This will help you keep track of and develop your ideas during your idea generation phase, and make it easier for others to give you feedback later on.

In addition to exploring our topic profiles, you could also identify questions through a literature review and reach out to your supervisor or other researchers in the field(s) you’re interested in and ask what they think some of the most important and neglected open questions are. Moreover, you could contact some of the organisations listed on our topic profiles and ask if there are research projects you could undertake that would be decision-relevant for them. Reaching out to others at this stage can also help to discard unfeasible ideas early on, before you invest too much time in them.

Some tools that might be useful during the idea generation phase:

- Connected papers – explore connections between research papers in a visual graph.

- Elicit – an AI research assistant to help you automate research workflows, like parts of literature review.

- Find more resources and tools for research here .

We recommend collecting at least 20 research questions, grouped into overarching topics or research fields, and then adding some context, e.g. relevant papers and researchers, why you think this question is worth addressing, what relevant expertise you already have, and how qualified you are to work on this compared to other options.

NB : We think that many people feel too limited by their past work, so we think you should probably lean towards considering questions and topics that are slightly outside your comfort zone.

Exercise: create a brainstorming document

Use this template to create a brainstorming document.

Comparing options

Once you feel you have collected enough research questions in your brainstorming document, you can start comparing how these research questions score on the factors that are most important to you. We recommend you take 15-20 minutes to think about which factors are key to your decision of pursuing a PhD and write them down. Here are some factors (adapted from this post ) that you could consider:

- Importance – How large in scale and/or severity is the problem your question would address?

- Tractability – How realistic is it that you would make progress? Is your research question concrete and manageable, and do you have a clear strategy to tackle it?

- Neglectedness – Will others work on this question if you don’t?

- Actionability – Would your research have a clear audience and could it inform positive actions? Will this project generate genuinely new and useful findings/data? Will it help to translate/ communicate important ideas that need more attention/ awareness?

- Learning value – Will you learn useful things from working on the project? Will it help you build valuable research skills, build your model of how something important works, and/ or help you refine a vaguely defined concept into a crisp, important question?

- Exploration value – Will this project help you decide what to do next?

- Personal fit & situational fit – Does your personal background make you a good fit for working on this question? Do you currently have or can you find support for working on it, e.g. excellent mentorship?

- Credentials and career capital – Will the output demonstrate your research competence? For example, if you could get a reference from a particularly prestigious researcher by working on one of the projects you’re interested in, this might be an important consideration. Will the project reflect well on you, and is it shareable with others (or could it be developed into something shareable/ a publication)? Will the project allow you to build relationships with people whom it will be helpful to know going forward?

- Intrinsic motivation – Are you excited about working on this project?

- Method efficacy – How well can a particular approach help solve the problem that you are trying to address?

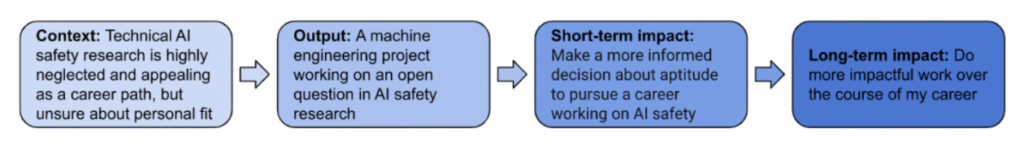

Exercise: sketch theories of change for your research questions

Once you’ve considered which of these factors matter to you, take a few minutes to sketch a theory of change for each research question you’re considering.

A theory of change is a step by step plan of how you hope to achieve a positive impact with your research, starting with the context you’d be working in, the research outputs you would plan to produce, and the short- and long-term impacts you would hope to achieve with your research. Sketching some theories of change will help you outline how your research ideas could have a positive impact, giving you something to get feedback on in the next step below.

Consider whether your research could have negative outcomes too

When you’re considering the value of working on a particular research problem, it may also be important to remember that research isn’t a monolithic force for good. Research has done a lot of good, but there are many examples of it doing a lot of harm as well. There is a long history of research being biased by the discriminatory beliefs and blindspots of its time, as well as being used to justify cruelty and oppression . Research has made warfare more deadly and has facilitated the development of intensive factory farming . Dual-use biotechnology research is intended to help humanity, but could, for example, cause a catastrophic pandemic in the event of a lab accident or if the technology was misused. While some researchers are trying to increase the chance that future artificial intelligence is safe for humanity , many more researchers are focused on making AI more powerful.

While it isn’t realistic for researchers to foresee every way their research could be (mis)used, many researchers are trying to create frameworks for thinking about how research can do harm and how to avoid this. For example, if you’re interested in working on biosecurity or AI safety, you could explore concepts such as differential progress and information hazards . If you’re working on global health questions, it may be important to educate yourself about the concept of parachute science .

Reach out to others for feedback

At this point, we think it could be helpful to identify some experts who might be interested in talking about your collection of potential research questions, and reach out to them for feedback. Getting feedback might then help you to prioritise between questions, develop your methodology further or discard projects before investing too much effort in them. You could seek feedback via two strategies – firstly, by sending your brainstorming document to people asking for general comments, and secondly, by seeking out people who have specialist knowledge on specific questions you’re considering and asking for their feedback on those ideas.

Here are some ways of connecting with other researchers:

- Reach out to your existing connections

- Attend research conferences related to your field of interest and speak to relevant people there, e.g. 1-1s at EAGs could be a great place to reach out to people for feedback on research ideas on directions that we recommend

- Are there any local student and/ or reading groups in your area that focus on a research area that you are planning to work on?

- Public Slack channels on your research area, e.g. List of EA Slack workspaces

When preparing to reach out to experts, keep these key points in mind:

- Give the expert relevant information about yourself (e.g. What is your background? What is the scope of the project you’re planning to work on?).

- Prepare a short agenda if they’ve agreed to call you and share it with them beforehand (although they might not have time to read it, many people appreciate having the option to consider topics of discussion in advance).

- Think about what your key uncertainties actually are and what kind of feedback you want from the expert. Would you like their overall reaction? Detailed comments? Feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of your research ideas? Specific suggestions to improve your ideas? Feedback on how you plan to use the outputs of your research project?

- Consider having a brainstorming document ready to share with them.

- You might want to have a look at this and this for more information about how to prepare.

Exercise: creating a weighted-factor model

Choosing which factors you want to base your thesis decision on will help you to reflect on what is important to you. Once you’ve done the exercise above and gathered some feedback from other people about your ideas, think about how much weight you want to give each factor. Lastly, try to evaluate how the research questions you’re considering score on each factor. The outcome of this ranking can serve as guidance for deciding on a question and can help clarify your intuitions about which questions would be the best fit for your dissertation. Here is an example of a ranking of potential thesis questions using a weighted-factor model (WFM).

Refining your research question

Once you have settled on a research question, it is time to develop a well-scoped and viable research proposal. The purpose of the proposal is to identify a relevant research topic, explain the context of the research, define concrete goals, and propose a realistic work plan to achieve them. If you’ve already built a Theory of Change for your research question, we recommend adding detail at this stage to help you create a proposal. We also think it’s important to reach out to your supervisor or other relevant people in the field of your research interests to ask for feedback, as this will help you develop an appropriate methodology.

Here are a few more tips that could help you with narrowing the scope of your research project or refining your research question:

- First, make sure you have a detailed model of the problem you are planning to address in your research. Who are the different actors involved? How can research help fill gaps in our current knowledge? What are the particularly neglected approaches and interventions for this problem?

- You will only be able to make a valuable research contribution if your project is focused. Break down goals into discrete tasks and summarise what you are actually going to do. We suggest you create a detailed plan for the first few months of your project, a less detailed but fully coherent plan for the first year, describe a direction you might take in the second year, and generate some ideas for the following years. This will help you understand how much work is involved in every step and evaluate what is feasible in the available time frame.

- Consider practical questions. What kind of facilities do you have? Do you meet the university requirements?

- Try to develop the smallest possible question that can be answered and that data can be collected on, then have conditional upgrades/sub-questions based on that. This can be ambitious, but each stage should be developed enough to not be overwhelming or too vague.

- Start with a research question that’s as simple as possible and that you’re confident will be successful. From there, you can slowly and incrementally work towards pursuing more complex research questions.

Find the best possible supportive environment

There are many different types of PhD programmes available – from 3-year PhDs to which you apply with a very specific project idea, to 6-year PhD programmes in which the first years are dedicated to coursework. It is important to find the best environment for your studies, with crucial considerations including the university and its community, the supportiveness of the supervisor/lab and the availability of funding. This section has advice on these three points and aims to facilitate you reflecting on them.

How much does the reputation of the university where you study your PhD matter for an academic career?

This is a commonly asked question among students, and we have compiled a set of key insights based on conversations with 30 of our experts.

- The general advice is that you should pick the most prestigious university or research hub that you can get into.

- The importance of your university’s reputation varies across regions, with the US and the UK placing more significance on it compared to Europe or Australia. For the US especially, you will likely get a much better education and teaching quality, as well as access to resources, from a more prestigious university.

- It is worth noting that high-quality research labs (and supervisors) can be found outside of big-name universities, as specific research hubs may exist elsewhere.

- It is important to note that even researchers in the most prestigious universities can be poor supervisors.

- Ideally, you’ll find a great supervisor at a highly reputable institution. However, if you have to decide, finding an excellent supervisor seems to be the superior consideration – see below.

- The significance of the university’s reputation increases if your career aspirations involve influencing government, e.g. in policy roles.

- Outstanding research, impactful contributions to the field, and a strong professional network could potentially outweigh the importance of a university’s reputation.

Find a standout advisor

We think it is very important to find someone who genuinely cares about your research question and who will make a lot of time to supervise you well. Further, your supervisor will influence how effective you are in your work and how much you enjoy the research, as they will be the primary person guiding you throughout your whole research process. Especially at the PhD level, your advisor’s network matters tremendously for how well- connected you are and what sorts of opportunities will be open to you. So, here are some green flags to look out for in a supervisor:

- They care about your research question (pitch your ideas to the supervisor and see how enthusiastic they are about the potential project).

- They have the skills to supervise your project (check if they have experience in the methodologies you want to use).

- They truly care about mentoring you well (ask questions about their mentoring style, get a feel for how you match as a person).

- Their previous and current students are satisfied with them as a supervisor (ideally the person has a good track record of supervising other students – arrange a meeting with at least one current or past student).

- They are successful (e.g. based on their citation count and general prestige).

Sign up for access to our database of potential supervisors who work on the research directions we recommend. Here are more tips on finding the right person to supervise you.

Financing your studies

Even if you get accepted to a programme, it does not automatically mean that you get funding as well. Here are some tips if you need to apply for funding independently:

Consider a wide range of funding sources, e.g. national scholarships, university scholarships, grants and foundations dedicated to specific causes, and excellence scholarships (e.g. Gates or Rhodes Scholarships). Here is our funding database which includes funding opportunities relevant to the research directions we recommend.

- Consider the university environment – Would you be happy to live in the city of the programme you are applying to for 3-6 years? Do some university environments offer a more stimulating environment than others? Are there other researchers with similar values or motivations to you in this research hub?

- Do you have any hard criteria for choosing the location for your PhD? For example, would you consider moving abroad for an exciting opportunity?

- What do you already know about the application process? What uncertainties do you have and how can you go about resolving them?

We recommend that you make a list of the programmes that best fit your research interests and other factors that are important to you. Then, check the requirements and deadlines for each of them and write down the next steps you need to take to apply. We also recommend reaching out to people who have gone through the PhD programme(s) you are applying to to hear about their experiences.

Set out your next steps

Take a few minutes now to write down your next steps for applying to the programs you’re interested in.

It could be helpful to sign up for some accountability buddy schemes, ask friends to check on your progress, or to set yourself a hard deadline on some important next steps that you want to take. You could schedule some time in your calendar right now, or make a note in your to-do list about a task that you want to complete soon.

Reflection prompts:

- What information do you need to get right now?

- What are you uncertain about?

- What is keeping you from advancing with your project and how could you concretely resolve this?

Examples for concrete next steps could be:

- Reach out to people for feedback on your brainstorming document

- Reach out to potential supervisors

- Apply to an EAG or other academic conference and make a list of people you want to speak to

- Reach out to people who have gone through the program you are applying to

- Reach out to current PhD students about proposal examples

Here are some further resources that could be helpful for you:

- Tips on impactful research

- Resources and tools for research

- Looking after your mental health

- Our Effective Thesis Community

- Research internships and other opportunities

For more general career advice, there are some other organisations that could help you with 1:1 advising. We recommend the following:

- 80,000 hours offers one-time 1:1 advising calls about using your career to help solve one of the world’s most pressing problems. They can help you choose your focus, make connections, and find a fulfilling job to tackle important problems.

- Magnify Mentoring pairs mentees who are interested in pursuing high-impact careers with more experienced mentors for a series of one-on-one meetings.

- Probably Good is running 1:1 advising calls to brainstorm career paths, evaluate options, plan next steps, and to connect you with relevant people and opportunities.

- Lastly, please leave us some feedback . Thank you!

Subscribe to the Topic Discovery Digest

Subscribe to our Topic Discovery Digest to find thesis topics, tools and resources that can help you significantly improve the world.

Apply for coaching

Want to work on one of our recommended research directions? Apply for coaching to receive personalised guidance.

Funding database

Find funding for your PhD on one of our recommended research directions.

Opportunities newsletter

Sign up to receive our fortnightly newsletter of personalised, research-related opportunities.

Sign up to access our database of potential supervisors

Sign up for access to our database of potential supervisors who work on the research directions we recommend.

Effective Thesis

Privacy policy

Stay in touch

Are you interested in applying for coaching or to our other services in future? Stay in touch and get our quarterly updates by signing up to our newsletter!

- Schools & departments

Writing a research proposal for the PhD in English Literature

You apply for the PhD in English Literature through the University’s online Degree Finder. Here is our guidance on how to write an effective application.

The two elements of an application that are most useful to us when we consider a candidate for the PhD in English Literature are the sample of written work and the research proposal.

You will probably choose your sample of written work from an already-completed undergraduate or masters-level dissertation or term-paper.

Your research proposal will be something new. It will describe the project that you want to complete for your PhD.

Your research proposal

Take your time in composing your research proposal, carefully considering the requirements outlined below. Your proposal should not be more than 2,000 words .

PhD degrees are awarded on the basis of a thesis of up to 100,000 words. The ‘Summary of roles and responsibilities’ in the University’s Code of Practice for Supervisors and Research Students stipulates what a research thesis must do.

Take me to the Code of Practice for Supervisors and Research Students (August 2020)

It is in the nature of research that, when you begin, you don’t know what you’ll find. This means that your project is bound to change over the time that you spend on it.

In submitting your research proposal, you are not committing yourself absolutely to completing exactly the project it describes in the event that you are accepted. Nevertheless, with the above points in mind, your research proposal should include the following elements, though not necessarily in this order:

1. An account of the body of primary texts that your thesis will examine. This may be work by one author, or several, or many, depending on the nature of the project. It is very unlikely to consist of a single text, however, unless that text is unusually compendious (The Canterbury Tales) or unusually demanding (Finnegans Wake). Unless your range of texts consists in the complete oeuvre of a single writer, you should explain why these texts are the ones that need to be examined in order to make your particular argument.

2. An identification of the existing field or fields of criticism and scholarship of which you will need to gain an ‘adequate knowledge’ in order to complete your thesis. This must include work in existing literary criticism, broadly understood. Usually this will consist of criticism or scholarship on the works or author(s) in question. In the case of very recent writing, or writing marginal to the established literary canon, on which there may be little or no existing critical work, it might include literary criticism written on other works or authors in the same period, or related work in the same mode or genre, or some other exercise of literary criticism that can serve as a reference point for your engagement with this new material.

The areas of scholarship on which you draw are also likely to include work in other disciplines, however. Most usually, these will be arguments in philosophy or critical theory that have informed, or could inform, the critical debate around your primary texts, or may have informed the texts themselves; and/or the historiography of the period in which your texts were written or received. But we are ready to consider the possible relevance of any other body of knowledge to literary criticism, as long as it is one with which you are sufficiently familiar, or could become sufficiently familiar within the period of your degree, for it to serve a meaningful role in your argument.

3. The questions or problems that the argument of your thesis will address; the methods you will adopt to answer those questions or explain those problems; and some explanation of why this particular methodology is the appropriate means of doing so. The problem could take many forms: a simple gap in the existing scholarship that you will fill; a misleading approach to the primary material that you will correct; or a difficulty in the relation of the existing scholarship to theoretical/philosophical, historiographical, or other disciplinary contexts, for example. But in any case, your thesis must engage critically with the scholarship of others by mounting an original argument in relation to the existing work in your field or fields. In this way your project must go beyond the summarising of already-existing knowledge.

4. Finally, your proposal should include a provisional timetable , describing the stages through which you hope your research will move over the course of your degree. It is crucial that, on the one hand, your chosen topic should be substantial enough to require around 80,000 words for its full exploration; and, on the other hand, that it has clear limits which would allow it to be completed in three years.

When drawing up this timetable, keep in mind that these word limits, and these time constraints, will require you to complete 25–30,000 words of your thesis in each of the years of your degree. If you intend to undertake your degree on a part-time basis, the amount of time available simply doubles.

In composing your research proposal you are already beginning the work that could lead, if you are accepted, to the award of a PhD degree. Regard it, then, as a chance to refine and focus your ideas, so that you can set immediately to work in an efficient manner on entry to university. But it bears repeating that that your project is bound to evolve beyond the project described in your proposal in ways that you cannot at this stage predict. No-one can know, when they begin any research work, where exactly it will take them. That provides much of the pleasure of research, for the most distinguished professor as much as for the first-year PhD student. If you are accepted as a candidate in this department, you will be joining a community of scholars still motivated by the thrill of finding and saying something new.

Ready to apply?

If you have read the guidance above and are ready to apply for your PhD in English Literature, you can do so online through the University of Edinburgh's Degree Finder.

Take me to the Degree Finder entry for the PhD in English Literature

If you've got any questions, please do not hesitate to contact Dr Aaron Kelly by email in the first instance.

Email Dr Aaron Kelly

We use cookies to help our site work, to understand how it is used, and to tailor ads that are more relevant to you and your interests.

By accepting, you agree to cookies being stored on your device. You can view details and manage settings at any time on our cookies policy page.

PhD English Literature

We perform innovative and world-leading research across literature, writing and linguistics. Our diverse mix of subject specialities means we are a vibrant and imaginative community with lots of opportunity for intellectual exchange.

Key course information

October 2024 - full-time, october 2024 - part-time, january 2025 - full-time, january 2025 - part-time, april 2025 - full-time, april 2025 - part-time, july 2025 - full-time, july 2025 - part-time, why choose this programme.

- We’re part of the interdisciplinary School of Literature and Languages, which has research-active staff who are at the forefront of knowledge in English literature, creative writing, film studies, translation studies, theoretical and applied linguistics, and literary and cultural studies.

- Our research concentrates on a range of periods, themes and subjects, spanning Medieval literature, Shakespeare and the Renaissance, Romanticism, Victorian and 19th-century literature, Modern and contemporary literature, creative writing and film studies.

- We’re part of TECHNE , an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)-funded doctoral training partnership, which provides access to comprehensive academic and professional training programmes, as well as the possibility of funding for your studies.

- The Research Excellence Framework (REF) 2021 ranked the School of Literature and Languages 10th for research impact in the UK, with 75% of our case studies rated as having outstanding impacts, in terms of reach and significance (4*). Our submission to REF included contributions from the Guildford School of Acting (GSA).

Fantastic graduate prospects

95% of Surrey's postgraduates go on to employment or further study

10th for Research impact

The Research Excellence Framework (REF) 2021 ranked the School of Literature and Languages

Programme details Open

What you will study.

Our English Literature PhD will train you in critical and analytical skills, research methods, and knowledge that will equip you for your professional or academic career. It normally takes around three or four years to complete our full-time PhD.

You’ll be assigned a primary and secondary supervisor, who will meet with you regularly to read and discuss your work and progress. For us, writing is essential for understanding and developing new perspectives, so you’ll be submitting written work right from the start of your course.

In the first year of your PhD, you’ll refine your research proposal and plan the structure of your work with the guidance and support of your supervisors. As you go into your second and third year, you’ll gradually learn to work more independently, and your supervisors will guide you on how to present at conferences and get your work published.

After 12-15 months, you’ll submit a substantial piece of work for a confirmation examination. The confirmation examination will be conducted by two internal members of staff not on your supervisory team and will give you the opportunity to gain additional guidance on your research-to-date. The final two years of your PhD will be devoted to expanding and refining your work ready for submission of the final thesis.

As a doctoral student in the School of Literature and Languages, you’ll receive a structured training programme covering the practical aspects of being a researcher, including grant-writing, publishing in journals, and applying for academic jobs.

Your final assessment will be based on the presentation of your research in a written thesis, which will be discussed in a viva examination with at least two examiners. You have the option of preparing your thesis as a monograph (one large volume in chapter form) or in publication format (including chapters written for publication), subject to the approval of your supervisors.

Stag Hill is the University's main campus and where the majority of our courses are taught.

Research areas Open

Research themes.

- Women's writing (especially medieval women's writing, early modern women's drama and Victorian women writers)

- Medieval romance

- Romanticism

- Victorian studies

- Modernism and modernity

- Travel and mobility

- Western and global esotericisms

- Sexuality and queer theory

- Postmodern and post-postmodern writing

- Contemporary fiction

- Transnational literature.

Discover more about our literature and languages research .

Academic staff Open

See a full list of all our literature and languages academic staff .

Support and facilities Open

Research support.

In addition to a number of excellent training opportunities offered by the University, our PhD students can take additional subject-specific training and take part in the School’s research seminars and events. These provide a valuable opportunity to meet visiting scholars whose work connects with our own research strengths across literature, theory, and creative writing.

The professional development of postgraduate researchers is supported by the Doctoral College , which provides training in essential skills through its Researcher Development Programme of workshops, mentoring and coaching. A dedicated postgraduate careers and employability team will help you prepare for a successful career after the completion of your PhD.

You’ll be allocated shared office space within the School of Literature and Languages and have full access to our library and online resources. Our close proximity to London also means that the British Library and many other important archives are within easy reach.

Hear from our students Open

Edwin Gilson

Student - English Literature PhD

"A real highlight for me was having an article published in a well-known journal in my field. This came out of a chapter I wasn’t expecting to write at the start of the thesis, on a novel I read during the PhD."

Entry requirements Open

Select your country, international students in the united kingdom.

Applicants are expected to hold a good first-class UK degree (a minimum 2:1 or equivalent) and an MA in a relevant topic.

English language requirements

IELTS Academic: 7.0 or above with a minimum of 6.5 in each component (or equivalent).

These are the English language qualifications and levels that we can accept.

If you do not currently meet the level required for your programme, we offer intensive pre-sessional English language courses , designed to take you to the level of English ability and skill required for your studies here.

Selection process

Selection is based on applicants:

- Meeting the expected entry requirements

- Being shortlisted through the application screening process

- Completing a successful interview

- Providing suitable references.

Fees and funding Open