- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

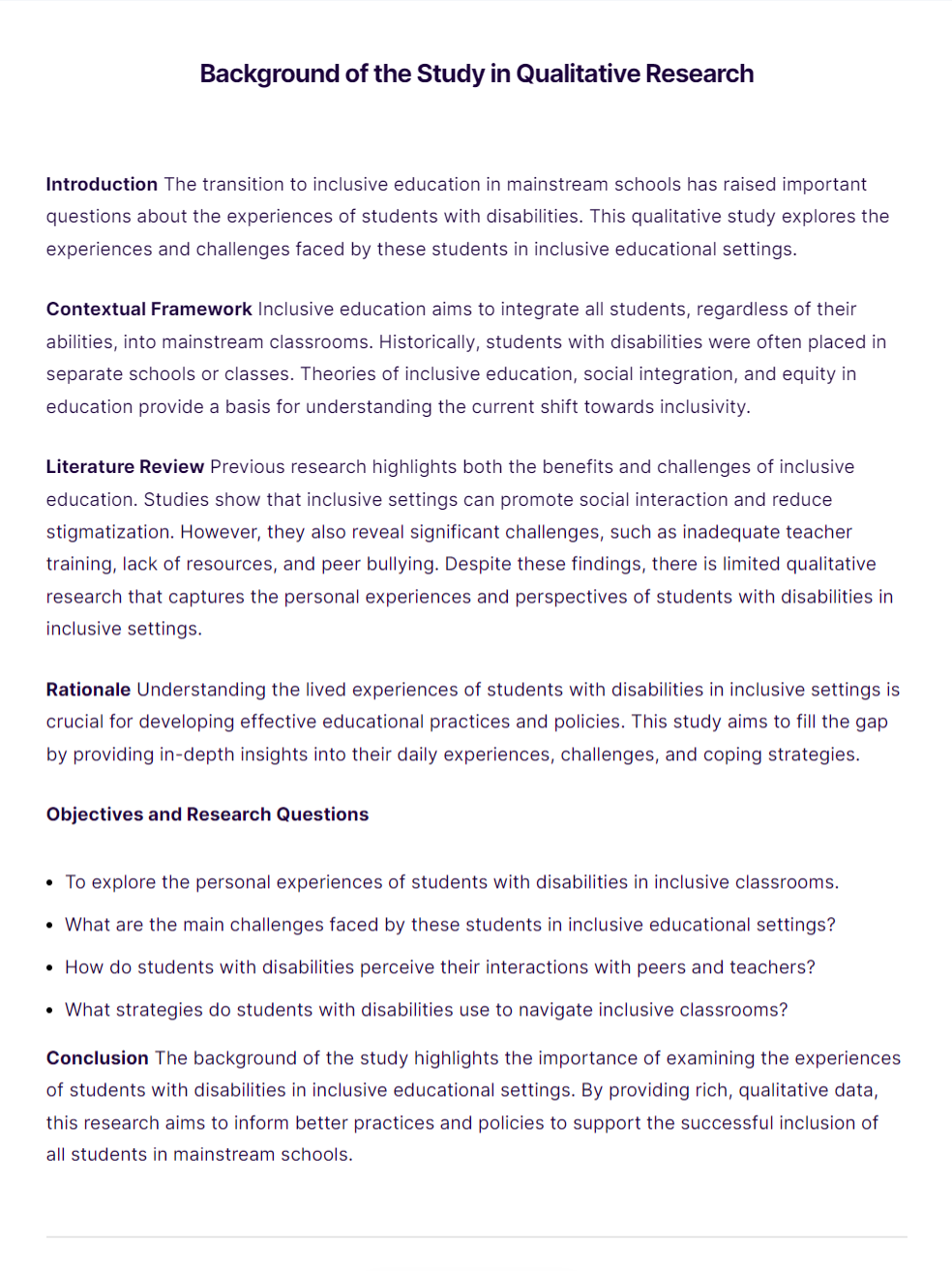

What is the Background of the Study and How to Write It

What is the Background of the Study in Research?

The background of the study is the first section of a research paper and gives context surrounding the research topic. The background explains to the reader where your research journey started, why you got interested in the topic, and how you developed the research question that you will later specify. That means that you first establish the context of the research you did with a general overview of the field or topic and then present the key issues that drove your decision to study the specific problem you chose.

Once the reader understands where you are coming from and why there was indeed a need for the research you are going to present in the following—because there was a gap in the current research, or because there is an obvious problem with a currently used process or technology—you can proceed with the formulation of your research question and summarize how you are going to address it in the rest of your manuscript.

Why is the Background of the Study Important?

No matter how surprising and important the findings of your study are, if you do not provide the reader with the necessary background information and context, they will not be able to understand your reasons for studying the specific problem you chose and why you think your study is relevant. And more importantly, an editor who does not share your enthusiasm for your work (because you did not fill them in on all the important details) will very probably not even consider your manuscript worthy of their and the reviewers’ time and will immediately send it back to you.

To avoid such desk rejections , you need to make sure you pique the reader’s interest and help them understand the contribution of your work to the specific field you study, the more general research community, or the public. Introducing the study background is crucial to setting the scene for your readers.

Table of Contents:

- What is “Background Information” in a Research Paper?

- What Should the Background of a Research Paper Include?

- Where Does the Background Section Go in Your Paper?

Background of the Study Structure

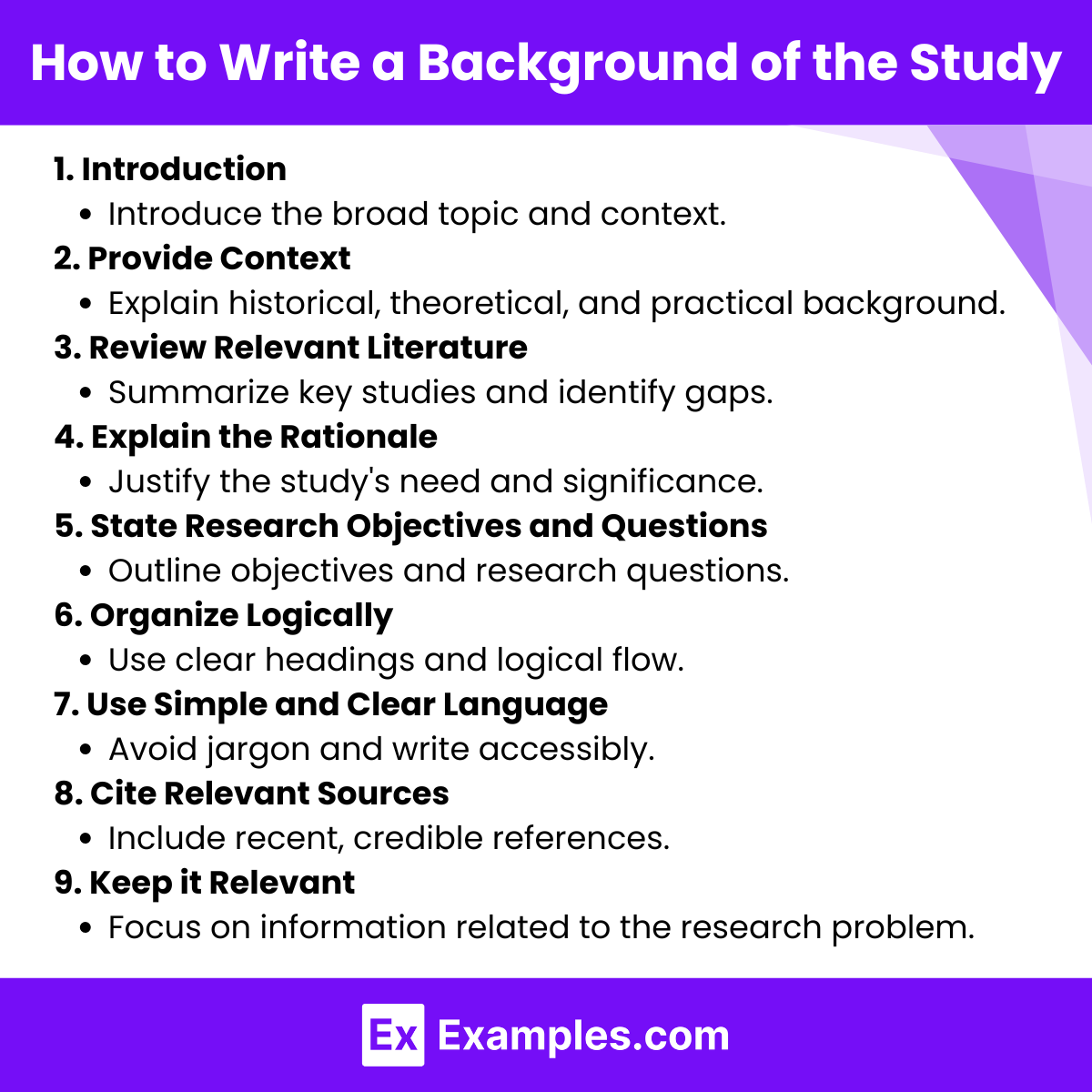

Before writing your study background, it is essential to understand what to include. The following elements should all be included in the background and are presented in greater detail in the next section:

- A general overview of the topic and why it is important (overlaps with establishing the “importance of the topic” in the Introduction)

- The current state of the research on the topic or on related topics in the field

- Controversies about current knowledge or specific past studies that undergird your research methodology

- Any claims or assumptions that have been made by researchers, institutions, or politicians that might need to be clarified

- Methods and techniques used in the study or from which your study deviated in some way

Presenting the Study Background

As you begin introducing your background, you first need to provide a general overview and include the main issues concerning the topic. Depending on whether you do “basic” (with the aim of providing further knowledge) or “applied” research (to establish new techniques, processes, or products), this is either a literature review that summarizes all relevant earlier studies in the field or a description of the process (e.g., vote counting) or practice (e.g., diagnosis of a specific disease) that you think is problematic or lacking and needs a solution.

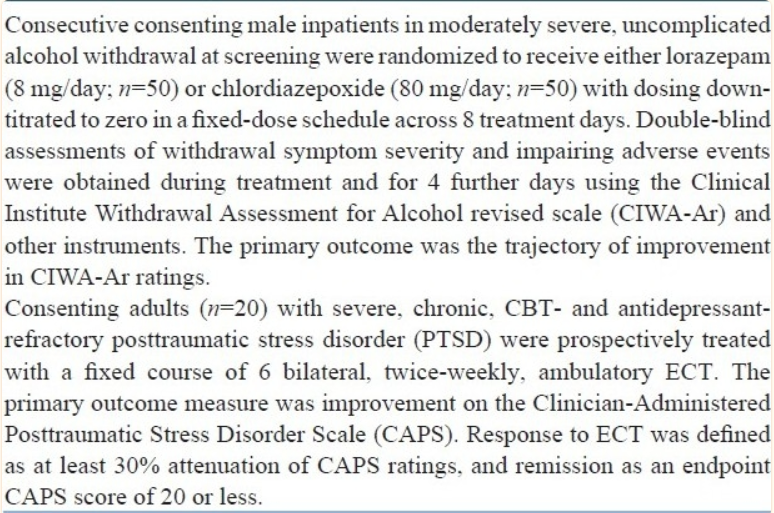

Example s of a general overview

If you study the function of a Drosophila gene, for example, you can explain to the reader why and for whom the study of fly genetics is relevant, what is already known and established, and where you see gaps in the existing literature. If you investigated how the way universities have transitioned into online teaching since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic has affected students’ learning progress, then you need to present a summary of what changes have happened around the world, what the effects of those changes have been so far, and where you see problems that need to be addressed. Note that you need to provide sources for every statement and every claim you make here, to establish a solid foundation of knowledge for your own study.

Describing the current state of knowledge

When the reader understands the main issue(s), you need to fill them in more specifically on the current state of the field (in basic research) or the process/practice/product use you describe (in practical/applied research). Cite all relevant studies that have already reported on the Drosophila gene you are interested in, have failed to reveal certain functions of it, or have suggested that it might be involved in more processes than we know so far. Or list the reports from the education ministries of the countries you are interested in and highlight the data that shows the need for research into the effects of the Corona-19 pandemic on teaching and learning.

Discussing controversies, claims, and assumptions

Are there controversies regarding your topic of interest that need to be mentioned and/or addressed? For example, if your research topic involves an issue that is politically hot, you can acknowledge this here. Have any earlier claims or assumptions been made, by other researchers, institutions, or politicians, that you think need to be clarified?

Mentioning methodologies and approaches

While putting together these details, you also need to mention methodologies : What methods/techniques have been used so far to study what you studied and why are you going to either use the same or a different approach? Are any of the methods included in the literature review flawed in such a way that your study takes specific measures to correct or update? While you shouldn’t spend too much time here justifying your methods (this can be summarized briefly in the rationale of the study at the end of the Introduction and later in the Discussion section), you can engage with the crucial methods applied in previous studies here first.

When you have established the background of the study of your research paper in such a logical way, then the reader should have had no problem following you from the more general information you introduced first to the specific details you added later. You can now easily lead over to the relevance of your research, explain how your work fits into the bigger picture, and specify the aims and objectives of your study. This latter part is usually considered the “ statement of the problem ” of your study. Without a solid research paper background, this statement will come out of nowhere for the reader and very probably raise more questions than you were planning to answer.

Where does the study background section go in a paper?

Unless you write a research proposal or some kind of report that has a specific “Background” chapter, the background of your study is the first part of your introduction section . This is where you put your work in context and provide all the relevant information the reader needs to follow your rationale. Make sure your background has a logical structure and naturally leads into the statement of the problem at the very end of the introduction so that you bring everything together for the reader to judge the relevance of your work and the validity of your approach before they dig deeper into the details of your study in the methods section .

Consider Receiving Professional Editing Services

Now that you know how to write a background section for a research paper, you might be interested in our AI Text Editor at Wordvice AI. And be sure to receive professional editing services , including academic editing and proofreading , before submitting your manuscript to journals. On the Wordvice academic resources website, you can also find many more articles and other resources that can help you with writing the other parts of your research paper , with making a research paper outline before you put everything together, or with writing an effective cover letter once you are ready to submit.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How to Write an Effective Background of the Study: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

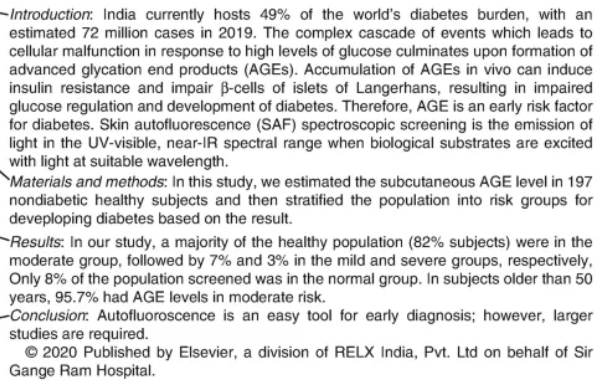

The background of the study in a research paper offers a clear context, highlighting why the research is essential and the problem it aims to address.

As a researcher, this foundational section is essential for you to chart the course of your study, Moreover, it allows readers to understand the importance and path of your research.

Whether in academic communities or to the general public, a well-articulated background aids in communicating the essence of the research effectively.

While it may seem straightforward, crafting an effective background requires a blend of clarity, precision, and relevance. Therefore, this article aims to be your guide, offering insights into:

- Understanding the concept of the background of the study.

- Learning how to craft a compelling background effectively.

- Identifying and sidestepping common pitfalls in writing the background.

- Exploring practical examples that bring the theory to life.

- Enhancing both your writing and reading of academic papers.

Keeping these compelling insights in mind, let's delve deeper into the details of the empirical background of the study, exploring its definition, distinctions, and the art of writing it effectively.

What is the background of the study?

The background of the study is placed at the beginning of a research paper. It provides the context, circumstances, and history that led to the research problem or topic being explored.

It offers readers a snapshot of the existing knowledge on the topic and the reasons that spurred your current research.

When crafting the background of your study, consider the following questions.

- What's the context of your research?

- Which previous research will you refer to?

- Are there any knowledge gaps in the existing relevant literature?

- How will you justify the need for your current research?

- Have you concisely presented the research question or problem?

In a typical research paper structure, after presenting the background, the introduction section follows. The introduction delves deeper into the specific objectives of the research and often outlines the structure or main points that the paper will cover.

Together, they create a cohesive starting point, ensuring readers are well-equipped to understand the subsequent sections of the research paper.

While the background of the study and the introduction section of the research manuscript may seem similar and sometimes even overlap, each serves a unique purpose in the research narrative.

Difference between background and introduction

A well-written background of the study and introduction are preliminary sections of a research paper and serve distinct purposes.

Here’s a detailed tabular comparison between the two of them.

Aspect | Background | Introduction |

Primary purpose | Provides context and logical reasons for the research, explaining why the study is necessary. | Entails the broader scope of the research, hinting at its objectives and significance. |

Depth of information | It delves into the existing literature, highlighting gaps or unresolved questions that the research aims to address. | It offers a general overview, touching upon the research topic without going into extensive detail. |

Content focus | The focus is on historical context, previous studies, and the evolution of the research topic. | The focus is on the broader research field, potential implications, and a preview of the research structure. |

Position in a research paper | Typically comes at the very beginning, setting the stage for the research. | Follows the background, leading readers into the main body of the research. |

Tone | Analytical, detailing the topic and its significance. | General and anticipatory, preparing readers for the depth and direction of the focus of the study. |

What is the relevance of the background of the study?

It is necessary for you to provide your readers with the background of your research. Without this, readers may grapple with questions such as: Why was this specific research topic chosen? What led to this decision? Why is this study relevant? Is it worth their time?

Such uncertainties can deter them from fully engaging with your study, leading to the rejection of your research paper. Additionally, this can diminish its impact in the academic community, and reduce its potential for real-world application or policy influence .

To address these concerns and offer clarity, the background section plays a pivotal role in research papers.

The background of the study in research is important as it:

- Provides context: It offers readers a clear picture of the existing knowledge, helping them understand where the current research fits in.

- Highlights relevance: By detailing the reasons for the research, it underscores the study's significance and its potential impact.

- Guides the narrative: The background shapes the narrative flow of the paper, ensuring a logical progression from what's known to what the research aims to uncover.

- Enhances engagement: A well-crafted background piques the reader's interest, encouraging them to delve deeper into the research paper.

- Aids in comprehension: By setting the scenario, it aids readers in better grasping the research objectives, methodologies, and findings.

How to write the background of the study in a research paper?

The journey of presenting a compelling argument begins with the background study. This section holds the power to either captivate or lose the reader's interest.

An effectively written background not only provides context but also sets the tone for the entire research paper. It's the bridge that connects a broad topic to a specific research question, guiding readers through the logic behind the study.

But how does one craft a background of the study that resonates, informs, and engages?

Here, we’ll discuss how to write an impactful background study, ensuring your research stands out and captures the attention it deserves.

Identify the research problem

The first step is to start pinpointing the specific issue or gap you're addressing. This should be a significant and relevant problem in your field.

A well-defined problem is specific, relevant, and significant to your field. It should resonate with both experts and readers.

Here’s more on how to write an effective research problem .

Provide context

Here, you need to provide a broader perspective, illustrating how your research aligns with or contributes to the overarching context or the wider field of study. A comprehensive context is grounded in facts, offers multiple perspectives, and is relatable.

In addition to stating facts, you should weave a story that connects key concepts from the past, present, and potential future research. For instance, consider the following approach.

- Offer a brief history of the topic, highlighting major milestones or turning points that have shaped the current landscape.

- Discuss contemporary developments or current trends that provide relevant information to your research problem. This could include technological advancements, policy changes, or shifts in societal attitudes.

- Highlight the views of different stakeholders. For a topic like sustainable agriculture, this could mean discussing the perspectives of farmers, environmentalists, policymakers, and consumers.

- If relevant, compare and contrast global trends with local conditions and circumstances. This can offer readers a more holistic understanding of the topic.

Literature review

For this step, you’ll deep dive into the existing literature on the same topic. It's where you explore what scholars, researchers, and experts have already discovered or discussed about your topic.

Conducting a thorough literature review isn't just a recap of past works. To elevate its efficacy, it's essential to analyze the methods, outcomes, and intricacies of prior research work, demonstrating a thorough engagement with the existing body of knowledge.

- Instead of merely listing past research study, delve into their methodologies, findings, and limitations. Highlight groundbreaking studies and those that had contrasting results.

- Try to identify patterns. Look for recurring themes or trends in the literature. Are there common conclusions or contentious points?

- The next step would be to connect the dots. Show how different pieces of research relate to each other. This can help in understanding the evolution of thought on the topic.

By showcasing what's already known, you can better highlight the background of the study in research.

Highlight the research gap

This step involves identifying the unexplored areas or unanswered questions in the existing literature. Your research seeks to address these gaps, providing new insights or answers.

A clear research gap shows you've thoroughly engaged with existing literature and found an area that needs further exploration.

How can you efficiently highlight the research gap?

- Find the overlooked areas. Point out topics or angles that haven't been adequately addressed.

- Highlight questions that have emerged due to recent developments or changing circumstances.

- Identify areas where insights from other fields might be beneficial but haven't been explored yet.

State your objectives

Here, it’s all about laying out your game plan — What do you hope to achieve with your research? You need to mention a clear objective that’s specific, actionable, and directly tied to the research gap.

How to state your objectives?

- List the primary questions guiding your research.

- If applicable, state any hypotheses or predictions you aim to test.

- Specify what you hope to achieve, whether it's new insights, solutions, or methodologies.

Discuss the significance

This step describes your 'why'. Why is your research important? What broader implications does it have?

The significance of “why” should be both theoretical (adding to the existing literature) and practical (having real-world implications).

How do we effectively discuss the significance?

- Discuss how your research adds to the existing body of knowledge.

- Highlight how your findings could be applied in real-world scenarios, from policy changes to on-ground practices.

- Point out how your research could pave the way for further studies or open up new areas of exploration.

Summarize your points

A concise summary acts as a bridge, smoothly transitioning readers from the background to the main body of the paper. This step is a brief recap, ensuring that readers have grasped the foundational concepts.

How to summarize your study?

- Revisit the key points discussed, from the research problem to its significance.

- Prepare the reader for the subsequent sections, ensuring they understand the research's direction.

Include examples for better understanding

Research and come up with real-world or hypothetical examples to clarify complex concepts or to illustrate the practical applications of your research. Relevant examples make abstract ideas tangible, aiding comprehension.

How to include an effective example of the background of the study?

- Use past events or scenarios to explain concepts.

- Craft potential scenarios to demonstrate the implications of your findings.

- Use comparisons to simplify complex ideas, making them more relatable.

Crafting a compelling background of the study in research is about striking the right balance between providing essential context, showcasing your comprehensive understanding of the existing literature, and highlighting the unique value of your research .

While writing the background of the study, keep your readers at the forefront of your mind. Every piece of information, every example, and every objective should be geared toward helping them understand and appreciate your research.

How to avoid mistakes in the background of the study in research?

To write a well-crafted background of the study, you should be aware of the following potential research pitfalls .

- Stay away from ambiguity. Always assume that your reader might not be familiar with intricate details about your topic.

- Avoid discussing unrelated themes. Stick to what's directly relevant to your research problem.

- Ensure your background is well-organized. Information should flow logically, making it easy for readers to follow.

- While it's vital to provide context, avoid overwhelming the reader with excessive details that might not be directly relevant to your research problem.

- Ensure you've covered the most significant and relevant studies i` n your field. Overlooking key pieces of literature can make your background seem incomplete.

- Aim for a balanced presentation of facts, and avoid showing overt bias or presenting only one side of an argument.

- While academic paper often involves specialized terms, ensure they're adequately explained or use simpler alternatives when possible.

- Every claim or piece of information taken from existing literature should be appropriately cited. Failing to do so can lead to issues of plagiarism.

- Avoid making the background too lengthy. While thoroughness is appreciated, it should not come at the expense of losing the reader's interest. Maybe prefer to keep it to one-two paragraphs long.

- Especially in rapidly evolving fields, it's crucial to ensure that your literature review section is up-to-date and includes the latest research.

Example of an effective background of the study

Let's consider a topic: "The Impact of Online Learning on Student Performance." The ideal background of the study section for this topic would be as follows.

In the last decade, the rise of the internet has revolutionized many sectors, including education. Online learning platforms, once a supplementary educational tool, have now become a primary mode of instruction for many institutions worldwide. With the recent global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a rapid shift from traditional classroom learning to online modes, making it imperative to understand its effects on student performance.

Previous studies have explored various facets of online learning, from its accessibility to its flexibility. However, there is a growing need to assess its direct impact on student outcomes. While some educators advocate for its benefits, citing the convenience and vast resources available, others express concerns about potential drawbacks, such as reduced student engagement and the challenges of self-discipline.

This research aims to delve deeper into this debate, evaluating the true impact of online learning on student performance.

Why is this example considered as an effective background section of a research paper?

This background section example effectively sets the context by highlighting the rise of online learning and its increased relevance due to recent global events. It references prior research on the topic, indicating a foundation built on existing knowledge.

By presenting both the potential advantages and concerns of online learning, it establishes a balanced view, leading to the clear purpose of the study: to evaluate the true impact of online learning on student performance.

As we've explored, writing an effective background of the study in research requires clarity, precision, and a keen understanding of both the broader landscape and the specific details of your topic.

From identifying the research problem, providing context, reviewing existing literature to highlighting research gaps and stating objectives, each step is pivotal in shaping the narrative of your research. And while there are best practices to follow, it's equally crucial to be aware of the pitfalls to avoid.

Remember, writing or refining the background of your study is essential to engage your readers, familiarize them with the research context, and set the ground for the insights your research project will unveil.

Drawing from all the important details, insights and guidance shared, you're now in a strong position to craft a background of the study that not only informs but also engages and resonates with your readers.

Now that you've a clear understanding of what the background of the study aims to achieve, the natural progression is to delve into the next crucial component — write an effective introduction section of a research paper. Read here .

Frequently Asked Questions

The background of the study should include a clear context for the research, references to relevant previous studies, identification of knowledge gaps, justification for the current research, a concise overview of the research problem or question, and an indication of the study's significance or potential impact.

The background of the study is written to provide readers with a clear understanding of the context, significance, and rationale behind the research. It offers a snapshot of existing knowledge on the topic, highlights the relevance of the study, and sets the stage for the research questions and objectives. It ensures that readers can grasp the importance of the research and its place within the broader field of study.

The background of the study is a section in a research paper that provides context, circumstances, and history leading to the research problem or topic being explored. It presents existing knowledge on the topic and outlines the reasons that spurred the current research, helping readers understand the research's foundation and its significance in the broader academic landscape.

The number of paragraphs in the background of the study can vary based on the complexity of the topic and the depth of the context required. Typically, it might range from 3 to 5 paragraphs, but in more detailed or complex research papers, it could be longer. The key is to ensure that all relevant information is presented clearly and concisely, without unnecessary repetition.

You might also like

Boosting Citations: A Comparative Analysis of Graphical Abstract vs. Video Abstract

The Impact of Visual Abstracts on Boosting Citations

Introducing SciSpace’s Citation Booster To Increase Research Visibility

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

What is the Background of a Study and How Should it be Written?

- 3 minute read

- 953.3K views

Table of Contents

The background of a study is one of the most important components of a research paper. The quality of the background determines whether the reader will be interested in the rest of the study. Thus, to ensure that the audience is invested in reading the entire research paper, it is important to write an appealing and effective background. So, what constitutes the background of a study, and how must it be written?

What is the background of a study?

The background of a study is the first section of the paper and establishes the context underlying the research. It contains the rationale, the key problem statement, and a brief overview of research questions that are addressed in the rest of the paper. The background forms the crux of the study because it introduces an unaware audience to the research and its importance in a clear and logical manner. At times, the background may even explore whether the study builds on or refutes findings from previous studies. Any relevant information that the readers need to know before delving into the paper should be made available to them in the background.

How is a background different from the introduction?

The introduction of your research paper is presented before the background. Let’s find out what factors differentiate the background from the introduction.

- The introduction only contains preliminary data about the research topic and does not state the purpose of the study. On the contrary, the background clarifies the importance of the study in detail.

- The introduction provides an overview of the research topic from a broader perspective, while the background provides a detailed understanding of the topic.

- The introduction should end with the mention of the research questions, aims, and objectives of the study. In contrast, the background follows no such format and only provides essential context to the study.

How should one write the background of a research paper?

The length and detail presented in the background varies for different research papers, depending on the complexity and novelty of the research topic. At times, a simple background suffices, even if the study is complex. Before writing and adding details in the background, take a note of these additional points:

- Start with a strong beginning: Begin the background by defining the research topic and then identify the target audience.

- Cover key components: Explain all theories, concepts, terms, and ideas that may feel unfamiliar to the target audience thoroughly.

- Take note of important prerequisites: Go through the relevant literature in detail. Take notes while reading and cite the sources.

- Maintain a balance: Make sure that the background is focused on important details, but also appeals to a broader audience.

- Include historical data: Current issues largely originate from historical events or findings. If the research borrows information from a historical context, add relevant data in the background.

- Explain novelty: If the research study or methodology is unique or novel, provide an explanation that helps to understand the research better.

- Increase engagement: To make the background engaging, build a story around the central theme of the research

Avoid these mistakes while writing the background:

- Ambiguity: Don’t be ambiguous. While writing, assume that the reader does not understand any intricate detail about your research.

- Unrelated themes: Steer clear from topics that are not related to the key aspects of your research topic.

- Poor organization: Do not place information without a structure. Make sure that the background reads in a chronological manner and organize the sub-sections so that it flows well.

Writing the background for a research paper should not be a daunting task. But directions to go about it can always help. At Elsevier Author Services we provide essential insights on how to write a high quality, appealing, and logically structured paper for publication, beginning with a robust background. For further queries, contact our experts now!

How to Use Tables and Figures effectively in Research Papers

The Top 5 Qualities of Every Good Researcher

You may also like.

Page-Turner Articles are More Than Just Good Arguments: Be Mindful of Tone and Structure!

A Must-see for Researchers! How to Ensure Inclusivity in Your Scientific Writing

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is the Background of a Study and How to Write It (Examples Included)

Have you ever found yourself struggling to write a background of the study for your research paper? You’re not alone. While the background of a study is an essential element of a research manuscript, it’s also one of the most challenging pieces to write. This is because it requires researchers to provide context and justification for their research, highlight the significance of their study, and situate their work within the existing body of knowledge in the field.

Despite its challenges, the background of a study is crucial for any research paper. A compelling well-written background of the study can not only promote confidence in the overall quality of your research analysis and findings, but it can also determine whether readers will be interested in knowing more about the rest of the research study.

In this article, we’ll explore the key elements of the background of a study and provide simple guidelines on how to write one effectively. Whether you’re a seasoned researcher or a graduate student working on your first research manuscript, this post will explain how to write a background for your study that is compelling and informative.

Table of Contents

What is the background of a study ?

Typically placed in the beginning of your research paper, the background of a study serves to convey the central argument of your study and its significance clearly and logically to an uninformed audience. The background of a study in a research paper helps to establish the research problem or gap in knowledge that the study aims to address, sets the stage for the research question and objectives, and highlights the significance of the research. The background of a study also includes a review of relevant literature, which helps researchers understand where the research study is placed in the current body of knowledge in a specific research discipline. It includes the reason for the study, the thesis statement, and a summary of the concept or problem being examined by the researcher. At times, the background of a study can may even examine whether your research supports or contradicts the results of earlier studies or existing knowledge on the subject.

How is the background of a study different from the introduction?

It is common to find early career researchers getting confused between the background of a study and the introduction in a research paper. Many incorrectly consider these two vital parts of a research paper the same and use these terms interchangeably. The confusion is understandable, however, it’s important to know that the introduction and the background of the study are distinct elements and serve very different purposes.

- The basic different between the background of a study and the introduction is kind of information that is shared with the readers . While the introduction provides an overview of the specific research topic and touches upon key parts of the research paper, the background of the study presents a detailed discussion on the existing literature in the field, identifies research gaps, and how the research being done will add to current knowledge.

- The introduction aims to capture the reader’s attention and interest and to provide a clear and concise summary of the research project. It typically begins with a general statement of the research problem and then narrows down to the specific research question. It may also include an overview of the research design, methodology, and scope. The background of the study outlines the historical, theoretical, and empirical background that led to the research question to highlight its importance. It typically offers an overview of the research field and may include a review of the literature to highlight gaps, controversies, or limitations in the existing knowledge and to justify the need for further research.

- Both these sections appear at the beginning of a research paper. In some cases the introduction may come before the background of the study , although in most instances the latter is integrated into the introduction itself. The length of the introduction and background of a study can differ based on the journal guidelines and the complexity of a specific research study.

Learn to convey study relevance, integrate literature reviews, and articulate research gaps in the background section. Get your All Access Pack now!

To put it simply, the background of the study provides context for the study by explaining how your research fills a research gap in existing knowledge in the field and how it will add to it. The introduction section explains how the research fills this gap by stating the research topic, the objectives of the research and the findings – it sets the context for the rest of the paper.

Where is the background of a study placed in a research paper?

T he background of a study is typically placed in the introduction section of a research paper and is positioned after the statement of the problem. Researchers should try and present the background of the study in clear logical structure by dividing it into several sections, such as introduction, literature review, and research gap. This will make it easier for the reader to understand the research problem and the motivation for the study.

So, when should you write the background of your study ? It’s recommended that researchers write this section after they have conducted a thorough literature review and identified the research problem, research question, and objectives. This way, they can effectively situate their study within the existing body of knowledge in the field and provide a clear rationale for their research.

Creating an effective background of a study structure

Given that the purpose of writing the background of your study is to make readers understand the reasons for conducting the research, it is important to create an outline and basic framework to work within. This will make it easier to write the background of the study and will ensure that it is comprehensive and compelling for readers.

While creating a background of the study structure for research papers, it is crucial to have a clear understanding of the essential elements that should be included. Make sure you incorporate the following elements in the background of the study section :

- Present a general overview of the research topic, its significance, and main aims; this may be like establishing the “importance of the topic” in the introduction.

- Discuss the existing level of research done on the research topic or on related topics in the field to set context for your research. Be concise and mention only the relevant part of studies, ideally in chronological order to reflect the progress being made.

- Highlight disputes in the field as well as claims made by scientists, organizations, or key policymakers that need to be investigated. This forms the foundation of your research methodology and solidifies the aims of your study.

- Describe if and how the methods and techniques used in the research study are different from those used in previous research on similar topics.

By including these critical elements in the background of your study , you can provide your readers with a comprehensive understanding of your research and its context.

How to write a background of the study in research papers ?

Now that you know the essential elements to include, it’s time to discuss how to write the background of the study in a concise and interesting way that engages audiences. The best way to do this is to build a clear narrative around the central theme of your research so that readers can grasp the concept and identify the gaps that the study will address. While the length and detail presented in the background of a study could vary depending on the complexity and novelty of the research topic, it is imperative to avoid wordiness. For research that is interdisciplinary, mentioning how the disciplines are connected and highlighting specific aspects to be studied helps readers understand the research better.

While there are different styles of writing the background of a study , it always helps to have a clear plan in place. Let us look at how to write a background of study for research papers.

- Identify the research problem: Begin the background by defining the research topic, and highlighting the main issue or question that the research aims to address. The research problem should be clear, specific, and relevant to the field of study. It should be framed using simple, easy to understand language and must be meaningful to intended audiences.

- Craft an impactful statement of the research objectives: While writing the background of the study it is critical to highlight the research objectives and specific goals that the study aims to achieve. The research objectives should be closely related to the research problem and must be aligned with the overall purpose of the study.

- Conduct a review of available literature: When writing the background of the research , provide a summary of relevant literature in the field and related research that has been conducted around the topic. Remember to record the search terms used and keep track of articles that you read so that sources can be cited accurately. Ensure that the literature you include is sourced from credible sources.

- Address existing controversies and assumptions: It is a good idea to acknowledge and clarify existing claims and controversies regarding the subject of your research. For example, if your research topic involves an issue that has been widely discussed due to ethical or politically considerations, it is best to address them when writing the background of the study .

- Present the relevance of the study: It is also important to provide a justification for the research. This is where the researcher explains why the study is important and what contributions it will make to existing knowledge on the subject. Highlighting key concepts and theories and explaining terms and ideas that may feel unfamiliar to readers makes the background of the study content more impactful.

- Proofread to eliminate errors in language, structure, and data shared: Once the first draft is done, it is a good idea to read and re-read the draft a few times to weed out possible grammatical errors or inaccuracies in the information provided. In fact, experts suggest that it is helpful to have your supervisor or peers read and edit the background of the study . Their feedback can help ensure that even inadvertent errors are not overlooked.

Get exclusive discounts on e xpert-led editing to publication support with Researcher.Life’s All Access Pack. Get yours now!

How to avoid mistakes in writing the background of a study

While figuring out how to write the background of a study , it is also important to know the most common mistakes authors make so you can steer clear of these in your research paper.

- Write the background of a study in a formal academic tone while keeping the language clear and simple. Check for the excessive use of jargon and technical terminology that could confuse your readers.

- Avoid including unrelated concepts that could distract from the subject of research. Instead, focus your discussion around the key aspects of your study by highlighting gaps in existing literature and knowledge and the novelty and necessity of your study.

- Provide relevant, reliable evidence to support your claims and citing sources correctly; be sure to follow a consistent referencing format and style throughout the paper.

- Ensure that the details presented in the background of the study are captured chronologically and organized into sub-sections for easy reading and comprehension.

- Check the journal guidelines for the recommended length for this section so that you include all the important details in a concise manner.

By keeping these tips in mind, you can create a clear, concise, and compelling background of the study for your research paper. Take this example of a background of the study on the impact of social media on mental health.

Social media has become a ubiquitous aspect of modern life, with people of all ages, genders, and backgrounds using platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter to connect with others, share information, and stay updated on news and events. While social media has many potential benefits, including increased social connectivity and access to information, there is growing concern about its impact on mental health. Research has suggested that social media use is associated with a range of negative mental health outcomes, including increased rates of anxiety, depression, and loneliness. This is thought to be due, in part, to the social comparison processes that occur on social media, whereby users compare their lives to the idealized versions of others that are presented online. Despite these concerns, there is also evidence to suggest that social media can have positive effects on mental health. For example, social media can provide a sense of social support and community, which can be beneficial for individuals who are socially isolated or marginalized. Given the potential benefits and risks of social media use for mental health, it is important to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying these effects. This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes, with a particular focus on the role of social comparison processes. By doing so, we hope to shed light on the potential risks and benefits of social media use for mental health, and to provide insights that can inform interventions and policies aimed at promoting healthy social media use.

To conclude, the background of a study is a crucial component of a research manuscript and must be planned, structured, and presented in a way that attracts reader attention, compels them to read the manuscript, creates an impact on the minds of readers and sets the stage for future discussions.

A well-written background of the study not only provides researchers with a clear direction on conducting their research, but it also enables readers to understand and appreciate the relevance of the research work being done.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on background of the study

Q: How does the background of the study help the reader understand the research better?

The background of the study plays a crucial role in helping readers understand the research better by providing the necessary context, framing the research problem, and establishing its significance. It helps readers:

- understand the larger framework, historical development, and existing knowledge related to a research topic

- identify gaps, limitations, or unresolved issues in the existing literature or knowledge

- outline potential contributions, practical implications, or theoretical advancements that the research aims to achieve

- and learn the specific context and limitations of the research project

Q: Does the background of the study need citation?

Yes, the background of the study in a research paper should include citations to support and acknowledge the sources of information and ideas presented. When you provide information or make statements in the background section that are based on previous studies, theories, or established knowledge, it is important to cite the relevant sources. This establishes credibility, enables verification, and demonstrates the depth of literature review you’ve done.

Q: What is the difference between background of the study and problem statement?

The background of the study provides context and establishes the research’s foundation while the problem statement clearly states the problem being addressed and the research questions or objectives.

Researcher.Life is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Researcher.Life All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 21+ years of experience in academia, Researcher.Life All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $17 a month !

Related Posts

What is a Case Study in Research? Definition, Methods, and Examples

How to Write an Academic Biography

How to Write Background of the Study Section in Research: 3 Tips

Learn how to craft a compelling Background of the Study section for your research paper with these 3 essential tips. Improve your academic writing skills and strengthen your research foundation.

Derek Pankaew

Jun 28, 2024

The background of the study is a crucial section in any research paper. It sets the stage for the research by providing context, explaining the significance, and highlighting the gaps that the study aims to fill. Crafting an effective background section can make a significant difference in how your research is perceived and understood. This article will provide three essential tips for writing a compelling background of the study: establishing the context, identifying the research gap, and justifying the significance of your study.

Tip 1: Establish the Context

Establishing the context is the first step in writing the background of a study. This involves providing a broad overview of the research topic, discussing relevant theories and concepts, and highlighting key studies in the field.

Provide a Broad Overview of the Research Topic

Begin the background by defining the research topic. This broad overview helps readers understand what your study is about and why it is important. Explain the central theme of your research, including the main issues or problems that led to the research. For instance, if your research topic involves an issue in public health, describe the current state of public health, including any prevailing trends, statistics, or significant changes that have occurred over time.

Discuss Relevant Theories and Concepts

Once you have set the stage with a broad overview, delve into the relevant theories and concepts in the literature review section. This section of a research paper should provide a theoretical framework that underpins your study. Discuss major theories that are relevant to your research topic and explain how they relate to your specific research problem or question, providing a solid theoretical base for your study background. This helps to anchor your research within a specific theoretical context, providing a foundation upon which your study in a research paper is built, serving as critical background information.

Highlight Key Studies in the Field

Highlighting key studies is essential for situating your research within the existing body of knowledge. Conduct a literature review to identify significant studies that have been conducted on your research topic. Summarize these studies, focusing on their findings and contributions to the field to enrich the literature review section of your research project. This not only demonstrates your understanding of the existing research but also helps to identify the gaps that your study aims to address, providing a strong background information context.

Tip 2: Identify the Research Gap

Identifying the research gap is a critical component of the background of the study. It involves analyzing existing literature critically, pointing out limitations or unanswered questions in current research, and explaining how your study addresses these gaps.

Analyze Existing Literature Critically

To identify the research gap, you need to analyze the existing literature critically. This involves more than just summarizing previous research; it requires a thorough examination of the strengths and weaknesses of existing studies in the context of your research objectives. Evaluate the methodologies used, the scope of the studies, and the robustness of their findings. This critical analysis will help you to pinpoint areas where further research is needed, thus setting clear research objectives.

Point Out Limitations or Unanswered Questions

Based on your analysis of the literature, identify the limitations or unanswered questions in current research. These could be methodological limitations, gaps in the data, or areas where existing studies have conflicting results. Highlight these gaps clearly, as they form the basis for your specific research problem or question. For example, if previous research has not adequately addressed a specific aspect of your research topic, point this out and explain why it is important to investigate further with a particular research question in mind.

Explain How Your Study Addresses These Gaps

After identifying the research gap, explain how your study aims to address it. Describe the unique approach or methodology that your study employs to fill these gaps, which are often detailed in the literature review section and background information. This section should clearly outline the objectives of your research and how they align with addressing the identified gaps. By doing so, you demonstrate the relevance and importance of your study in advancing the field, which is essential when you write a background.

Tip 3: Justify the Significance of Your Study

Justifying the significance of your study is the final tip for writing an effective background section. This involves explaining the potential impact of your research, connecting your study to real-world applications or problems, and emphasizing the novelty or unique approach of your study mentioned in the introduction section.

Explain the Potential Impact of Your Research

Begin by explaining the potential impact of your research on the background of your study, setting the stage for your research aims. This involves discussing the broader implications of your study and how it contributes to the field of study. Describe how your findings could influence future research, policy-making, or practice. For instance, if your research addresses a significant public health issue, explain how your findings could inform public health policies or interventions.

Connect Your Study to Real-World Applications or Problems

Next, connect your study to real-world applications or problems. This helps to demonstrate the practical relevance of your research, a crucial aspect when you write a research paper to show its significance. Describe specific examples of how your research could be applied in real-world scenarios, illustrating the practical implications in the study background information section. For instance, if your study involves developing a new technology, explain how this technology could be used in industry or by consumers. This connection to real-world applications makes your research more tangible and relevant to a broader audience, demonstrating the potential impact of your research study. When you write a research paper, highlighting these connections can be crucial.

Emphasize the Novelty or Unique Approach of Your Study

Finally, emphasize the novelty or unique approach of your study, which is a key element in the introduction section. Highlight what makes your research different from previous studies and why this is important to understand the research in the context of your research aims. This could involve a novel methodology, a new theoretical perspective, or a unique combination of variables, all contributing to a well-defined research study. By emphasizing the uniqueness of your study, you underscore its contribution to the field and its potential to advance knowledge, specifically addressing a particular research question. This understanding is essential when learning how to write a research study.

In conclusion, writing an effective background for the study is crucial for setting the stage for your research paper. By following these three tips—establishing the context, identifying the research gap, and justifying the significance of your study—you can craft a compelling background section that clearly articulates the importance and relevance of your research. A well-written background not only provides context and justification for your study but also engages your readers and sets the stage for the rest of your research paper.

Easily pronounces technical words in any field

Research Writing

Academic Tips

Background Study

Research Methodology

Scholarly Communication

Recent articles

11 Companies that Offer Internships to Engineering Majors

Amethyst Rayne

Jul 2, 2024

Mentorship programs

Engineering internships

Internship opportunities

Career development

Natural Reader vs Listening.com: Which Text To Speech App is Better?

Glice Martineau

8 Educational Podcasts Every College Student Should Listen To

Jul 3, 2024

Educational podcasts

College student tips

Best podcasts 2024

Student productivity

Personal growth

What are Cool Summer Jobs for College Students? 10 Ideas

Student Employment

Career Advice

College Students

Summer Jobs

What Is Background in a Research Paper?

So you have carefully written your research paper and probably ran it through your colleagues ten to fifteen times. While there are many elements to a good research article, one of the most important elements for your readers is the background of your study.

What is Background of the Study in Research

The background of your study will provide context to the information discussed throughout the research paper . Background information may include both important and relevant studies. This is particularly important if a study either supports or refutes your thesis.

Why is Background of the Study Necessary in Research?

The background of the study discusses your problem statement, rationale, and research questions. It links introduction to your research topic and ensures a logical flow of ideas. Thus, it helps readers understand your reasons for conducting the study.

Providing Background Information

The reader should be able to understand your topic and its importance. The length and detail of your background also depend on the degree to which you need to demonstrate your understanding of the topic. Paying close attention to the following questions will help you in writing background information:

- Are there any theories, concepts, terms, and ideas that may be unfamiliar to the target audience and will require you to provide any additional explanation?

- Any historical data that need to be shared in order to provide context on why the current issue emerged?

- Are there any concepts that may have been borrowed from other disciplines that may be unfamiliar to the reader and need an explanation?

Related: Ready with the background and searching for more information on journal ranking? Check this infographic on the SCImago Journal Rank today!

Is the research study unique for which additional explanation is needed? For instance, you may have used a completely new method

How to Write a Background of the Study

The structure of a background study in a research paper generally follows a logical sequence to provide context, justification, and an understanding of the research problem. It includes an introduction, general background, literature review , rationale , objectives, scope and limitations , significance of the study and the research hypothesis . Following the structure can provide a comprehensive and well-organized background for your research.

Here are the steps to effectively write a background of the study.

1. Identify Your Audience:

Determine the level of expertise of your target audience. Tailor the depth and complexity of your background information accordingly.

2. Understand the Research Problem:

Define the research problem or question your study aims to address. Identify the significance of the problem within the broader context of the field.

3. Review Existing Literature:

Conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known in the area. Summarize key findings, theories, and concepts relevant to your research.

4. Include Historical Data:

Integrate historical data if relevant to the research, as current issues often trace back to historical events.

5. Identify Controversies and Gaps:

Note any controversies or debates within the existing literature. Identify gaps , limitations, or unanswered questions that your research can address.

6. Select Key Components:

Choose the most critical elements to include in the background based on their relevance to your research problem. Prioritize information that helps build a strong foundation for your study.

7. Craft a Logical Flow:

Organize the background information in a logical sequence. Start with general context, move to specific theories and concepts, and then focus on the specific problem.

8. Highlight the Novelty of Your Research:

Clearly explain the unique aspects or contributions of your study. Emphasize why your research is different from or builds upon existing work.

Here are some extra tips to increase the quality of your research background:

Example of a Research Background

Here is an example of a research background to help you understand better.

The above hypothetical example provides a research background, addresses the gap and highlights the potential outcome of the study; thereby aiding a better understanding of the proposed research.

What Makes the Introduction Different from the Background?

Your introduction is different from your background in a number of ways.

- The introduction contains preliminary data about your topic that the reader will most likely read , whereas the background clarifies the importance of the paper.

- The background of your study discusses in depth about the topic, whereas the introduction only gives an overview.

- The introduction should end with your research questions, aims, and objectives, whereas your background should not (except in some cases where your background is integrated into your introduction). For instance, the C.A.R.S. ( Creating a Research Space ) model, created by John Swales is based on his analysis of journal articles. This model attempts to explain and describe the organizational pattern of writing the introduction in social sciences.

Points to Note

Your background should begin with defining a topic and audience. It is important that you identify which topic you need to review and what your audience already knows about the topic. You should proceed by searching and researching the relevant literature. In this case, it is advisable to keep track of the search terms you used and the articles that you downloaded. It is helpful to use one of the research paper management systems such as Papers, Mendeley, Evernote, or Sente. Next, it is helpful to take notes while reading. Be careful when copying quotes verbatim and make sure to put them in quotation marks and cite the sources. In addition, you should keep your background focused but balanced enough so that it is relevant to a broader audience. Aside from these, your background should be critical, consistent, and logically structured.

Writing the background of your study should not be an overly daunting task. Many guides that can help you organize your thoughts as you write the background. The background of the study is the key to introduce your audience to your research topic and should be done with strong knowledge and thoughtful writing.

The background of a research paper typically ranges from one to two paragraphs, summarizing the relevant literature and context of the study. It should be concise, providing enough information to contextualize the research problem and justify the need for the study. Journal instructions about any word count limits should be kept in mind while deciding on the length of the final content.

The background of a research paper provides the context and relevant literature to understand the research problem, while the introduction also introduces the specific research topic, states the research objectives, and outlines the scope of the study. The background focuses on the broader context, whereas the introduction focuses on the specific research project and its objectives.

When writing the background for a study, start by providing a brief overview of the research topic and its significance in the field. Then, highlight the gaps in existing knowledge or unresolved issues that the study aims to address. Finally, summarize the key findings from relevant literature to establish the context and rationale for conducting the research, emphasizing the need and importance of the study within the broader academic landscape.

The background in a research paper is crucial as it sets the stage for the study by providing essential context and rationale. It helps readers understand the significance of the research problem and its relevance in the broader field. By presenting relevant literature and highlighting gaps, the background justifies the need for the study, building a strong foundation for the research and enhancing its credibility.

The presentation very informative

It is really educative. I love the workshop. It really motivated me into writing my first paper for publication.

an interesting clue here, thanks.

thanks for the answers.

Good and interesting explanation. Thanks

Thank you for good presentation.

Hi Adam, we are glad to know that you found our article beneficial

The background of the study is the key to introduce your audience to YOUR research topic.

Awesome. Exactly what i was looking forwards to 😉

Hi Maryam, we are glad to know that you found our resource useful.

my understanding of ‘Background of study’ has been elevated.

Hi Peter, we are glad to know that our article has helped you get a better understanding of the background in a research paper.

thanks to give advanced information

Hi Shimelis, we are glad to know that you found the information in our article beneficial.

When i was studying it is very much hard for me to conduct a research study and know the background because my teacher in practical research is having a research so i make it now so that i will done my research

Very informative……….Thank you.

The confusion i had before, regarding an introduction and background to a research work is now a thing of the past. Thank you so much.

Thanks for your help…

Thanks for your kind information about the background of a research paper.

Thanks for the answer

Very informative. I liked even more when the difference between background and introduction was given. I am looking forward to learning more from this site. I am in Botswana

Hello, I am Benoît from Central African Republic. Right now I am writing down my research paper in order to get my master degree in British Literature. Thank you very much for posting all this information about the background of the study. I really appreciate. Thanks!

The write up is quite good, detailed and informative. Thanks a lot. The article has certainly enhanced my understanding of the topic.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

- Infographic

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Reporting Research

- Trending Now

Can AI Tools Prepare a Research Manuscript From Scratch? — A comprehensive guide

As technology continues to advance, the question of whether artificial intelligence (AI) tools can prepare…

Abstract Vs. Introduction — Do you know the difference?

Ross wants to publish his research. Feeling positive about his research outcomes, he begins to…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Demystifying Research Methodology With Field Experts

Choosing research methodology Research design and methodology Evidence-based research approach How RAxter can assist researchers

- Manuscript Preparation

- Publishing Research

How to Choose Best Research Methodology for Your Study

Successful research conduction requires proper planning and execution. While there are multiple reasons and aspects…

Top 5 Key Differences Between Methods and Methodology

While burning the midnight oil during literature review, most researchers do not realize that the…

How to Draft the Acknowledgment Section of a Manuscript

Discussion Vs. Conclusion: Know the Difference Before Drafting Manuscripts

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What would be most effective in reducing research misconduct?

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Background Information

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Background information identifies and describes the history and nature of a well-defined research problem with reference to contextualizing existing literature. The background information should indicate the root of the problem being studied, appropriate context of the problem in relation to theory, research, and/or practice , its scope, and the extent to which previous studies have successfully investigated the problem, noting, in particular, where gaps exist that your study attempts to address. Background information does not replace the literature review section of a research paper; it is intended to place the research problem within a specific context and an established plan for its solution.

Fitterling, Lori. Researching and Writing an Effective Background Section of a Research Paper. Kansas City University of Medicine & Biosciences; Creating a Research Paper: How to Write the Background to a Study. DurousseauElectricalInstitute.com; Background Information: Definition of Background Information. Literary Devices Definition and Examples of Literary Terms.

Importance of Having Enough Background Information

Background information expands upon the key points stated in the beginning of your introduction but is not intended to be the main focus of the paper. It generally supports the question, what is the most important information the reader needs to understand before continuing to read the paper? Sufficient background information helps the reader determine if you have a basic understanding of the research problem being investigated and promotes confidence in the overall quality of your analysis and findings. This information provides the reader with the essential context needed to conceptualize the research problem and its significance before moving on to a more thorough analysis of prior research.

Forms of contextualization included in background information can include describing one or more of the following:

- Cultural -- placed within the learned behavior of a specific group or groups of people.

- Economic -- of or relating to systems of production and management of material wealth and/or business activities.

- Gender -- located within the behavioral, cultural, or psychological traits typically associated with being self-identified as male, female, or other form of gender expression.

- Historical -- the time in which something takes place or was created and how the condition of time influences how you interpret it.

- Interdisciplinary -- explanation of theories, concepts, ideas, or methodologies borrowed from other disciplines applied to the research problem rooted in a discipline other than the discipline where your paper resides.

- Philosophical -- clarification of the essential nature of being or of phenomena as it relates to the research problem.

- Physical/Spatial -- reflects the meaning of space around something and how that influences how it is understood.

- Political -- concerns the environment in which something is produced indicating it's public purpose or agenda.

- Social -- the environment of people that surrounds something's creation or intended audience, reflecting how the people associated with something use and interpret it.

- Temporal -- reflects issues or events of, relating to, or limited by time. Concerns past, present, or future contextualization and not just a historical past.

Background information can also include summaries of important research studies . This can be a particularly important element of providing background information if an innovative or groundbreaking study about the research problem laid a foundation for further research or there was a key study that is essential to understanding your arguments. The priority is to summarize for the reader what is known about the research problem before you conduct the analysis of prior research. This is accomplished with a general summary of the foundational research literature [with citations] that document findings that inform your study's overall aims and objectives.

NOTE: Research studies cited as part of the background information of your introduction should not include very specific, lengthy explanations. This should be discussed in greater detail in your literature review section. If you find a study requiring lengthy explanation, consider moving it to the literature review section.

ANOTHER NOTE: In some cases, your paper's introduction only needs to introduce the research problem, explain its significance, and then describe a road map for how you are going to address the problem; the background information basically forms the introduction part of your literature review. That said, while providing background information is not required, including it in the introduction is a way to highlight important contextual information that could otherwise be hidden or overlooked by the reader if placed in the literature review section.

YET ANOTHER NOTE: In some research studies, the background information is described in a separate section after the introduction and before the literature review. This is most often done if the topic is especially complex or requires a lot of context in order to fully grasp the significance of the research problem. Most college-level research papers do not require this unless required by your professor. However, if you find yourself needing to write more than a couple of pages [double-spaced lines] to provide the background information, it can be written as a separate section to ensure the introduction is not too lengthy.