Qualitative Research: Characteristics, Design, Methods & Examples

Lauren McCall

MSc Health Psychology Graduate

MSc, Health Psychology, University of Nottingham

Lauren obtained an MSc in Health Psychology from The University of Nottingham with a distinction classification.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on gathering and analyzing non-numerical data to gain a deeper understanding of human behavior, experiences, and perspectives.

It aims to explore the “why” and “how” of a phenomenon rather than the “what,” “where,” and “when” typically addressed by quantitative research.

Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on gathering and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis, qualitative research involves researchers interpreting data to identify themes, patterns, and meanings.

Qualitative research can be used to:

- Gain deep contextual understandings of the subjective social reality of individuals

- To answer questions about experience and meaning from the participant’s perspective

- To design hypotheses, theory must be researched using qualitative methods to determine what is important before research can begin.

Examples of qualitative research questions include:

- How does stress influence young adults’ behavior?

- What factors influence students’ school attendance rates in developed countries?

- How do adults interpret binge drinking in the UK?

- What are the psychological impacts of cervical cancer screening in women?

- How can mental health lessons be integrated into the school curriculum?

Characteristics

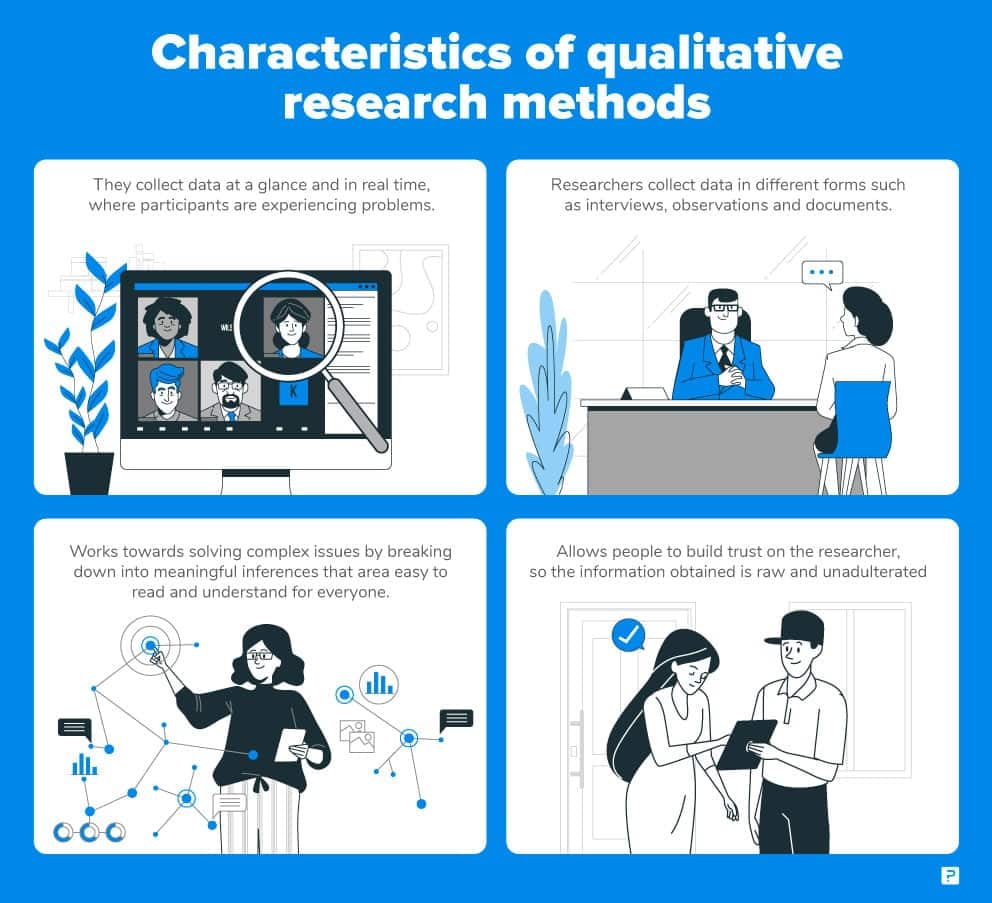

Naturalistic setting.

Individuals are studied in their natural setting to gain a deeper understanding of how people experience the world. This enables the researcher to understand a phenomenon close to how participants experience it.

Naturalistic settings provide valuable contextual information to help researchers better understand and interpret the data they collect.

The environment, social interactions, and cultural factors can all influence behavior and experiences, and these elements are more easily observed in real-world settings.

Reality is socially constructed

Qualitative research aims to understand how participants make meaning of their experiences – individually or in social contexts. It assumes there is no objective reality and that the social world is interpreted (Yilmaz, 2013).

The primacy of subject matter

The primary aim of qualitative research is to understand the perspectives, experiences, and beliefs of individuals who have experienced the phenomenon selected for research rather than the average experiences of groups of people (Minichiello, 1990).

An in-depth understanding is attained since qualitative techniques allow participants to freely disclose their experiences, thoughts, and feelings without constraint (Tenny et al., 2022).

Variables are complex, interwoven, and difficult to measure

Factors such as experiences, behaviors, and attitudes are complex and interwoven, so they cannot be reduced to isolated variables , making them difficult to measure quantitatively.

However, a qualitative approach enables participants to describe what, why, or how they were thinking/ feeling during a phenomenon being studied (Yilmaz, 2013).

Emic (insider’s point of view)

The phenomenon being studied is centered on the participants’ point of view (Minichiello, 1990).

Emic is used to describe how participants interact, communicate, and behave in the research setting (Scarduzio, 2017).

Interpretive analysis

In qualitative research, interpretive analysis is crucial in making sense of the collected data.

This process involves examining the raw data, such as interview transcripts, field notes, or documents, and identifying the underlying themes, patterns, and meanings that emerge from the participants’ experiences and perspectives.

Collecting Qualitative Data

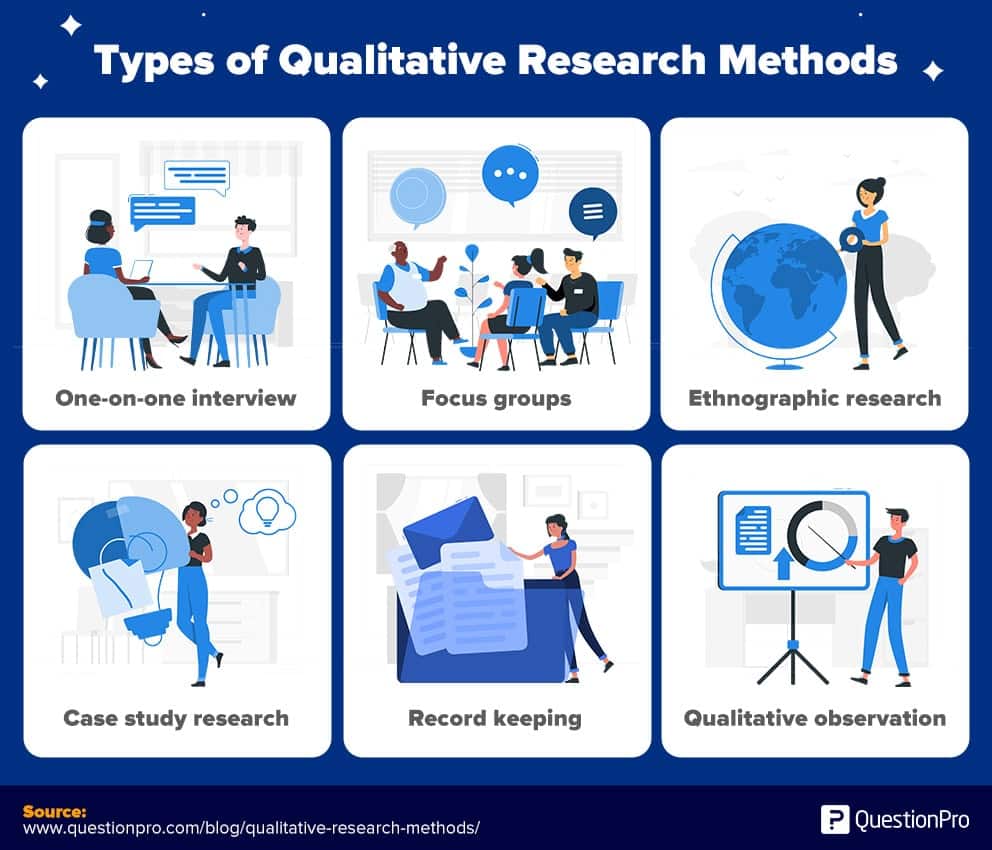

There are four main research design methods used to collect qualitative data: observations, interviews, focus groups, and ethnography.

Observations

This method involves watching and recording phenomena as they occur in nature. Observation can be divided into two types: participant and non-participant observation.

In participant observation, the researcher actively participates in the situation/events being observed.

In non-participant observation, the researcher is not an active part of the observation and tries not to influence the behaviors they are observing (Busetto et al., 2020).

Observations can be covert (participants are unaware that a researcher is observing them) or overt (participants are aware of the researcher’s presence and know they are being observed).

However, awareness of an observer’s presence may influence participants’ behavior.

Interviews give researchers a window into the world of a participant by seeking their account of an event, situation, or phenomenon. They are usually conducted on a one-to-one basis and can be distinguished according to the level at which they are structured (Punch, 2013).

Structured interviews involve predetermined questions and sequences to ensure replicability and comparability. However, they are unable to explore emerging issues.

Informal interviews consist of spontaneous, casual conversations which are closer to the truth of a phenomenon. However, information is gathered using quick notes made by the researcher and is therefore subject to recall bias.

Semi-structured interviews have a flexible structure, phrasing, and placement so emerging issues can be explored (Denny & Weckesser, 2022).

The use of probing questions and clarification can lead to a detailed understanding, but semi-structured interviews can be time-consuming and subject to interviewer bias.

Focus groups

Similar to interviews, focus groups elicit a rich and detailed account of an experience. However, focus groups are more dynamic since participants with shared characteristics construct this account together (Denny & Weckesser, 2022).

A shared narrative is built between participants to capture a group experience shaped by a shared context.

The researcher takes on the role of a moderator, who will establish ground rules and guide the discussion by following a topic guide to focus the group discussions.

Typically, focus groups have 4-10 participants as a discussion can be difficult to facilitate with more than this, and this number allows everyone the time to speak.

Ethnography

Ethnography is a methodology used to study a group of people’s behaviors and social interactions in their environment (Reeves et al., 2008).

Data are collected using methods such as observations, field notes, or structured/ unstructured interviews.

The aim of ethnography is to provide detailed, holistic insights into people’s behavior and perspectives within their natural setting. In order to achieve this, researchers immerse themselves in a community or organization.

Due to the flexibility and real-world focus of ethnography, researchers are able to gather an in-depth, nuanced understanding of people’s experiences, knowledge and perspectives that are influenced by culture and society.

In order to develop a representative picture of a particular culture/ context, researchers must conduct extensive field work.

This can be time-consuming as researchers may need to immerse themselves into a community/ culture for a few days, or possibly a few years.

Qualitative Data Analysis Methods

Different methods can be used for analyzing qualitative data. The researcher chooses based on the objectives of their study.

The researcher plays a key role in the interpretation of data, making decisions about the coding, theming, decontextualizing, and recontextualizing of data (Starks & Trinidad, 2007).

Grounded theory

Grounded theory is a qualitative method specifically designed to inductively generate theory from data. It was developed by Glaser and Strauss in 1967 (Glaser & Strauss, 2017).

This methodology aims to develop theories (rather than test hypotheses) that explain a social process, action, or interaction (Petty et al., 2012). To inform the developing theory, data collection and analysis run simultaneously.

There are three key types of coding used in grounded theory: initial (open), intermediate (axial), and advanced (selective) coding.

Throughout the analysis, memos should be created to document methodological and theoretical ideas about the data. Data should be collected and analyzed until data saturation is reached and a theory is developed.

Content analysis

Content analysis was first used in the early twentieth century to analyze textual materials such as newspapers and political speeches.

Content analysis is a research method used to identify and analyze the presence and patterns of themes, concepts, or words in data (Vaismoradi et al., 2013).

This research method can be used to analyze data in different formats, which can be written, oral, or visual.

The goal of content analysis is to develop themes that capture the underlying meanings of data (Schreier, 2012).

Qualitative content analysis can be used to validate existing theories, support the development of new models and theories, and provide in-depth descriptions of particular settings or experiences.

The following six steps provide a guideline for how to conduct qualitative content analysis.

- Define a Research Question : To start content analysis, a clear research question should be developed.

- Identify and Collect Data : Establish the inclusion criteria for your data. Find the relevant sources to analyze.

- Define the Unit or Theme of Analysis : Categorize the content into themes. Themes can be a word, phrase, or sentence.

- Develop Rules for Coding your Data : Define a set of coding rules to ensure that all data are coded consistently.

- Code the Data : Follow the coding rules to categorize data into themes.

- Analyze the Results and Draw Conclusions : Examine the data to identify patterns and draw conclusions in relation to your research question.

Discourse analysis

Discourse analysis is a research method used to study written/ spoken language in relation to its social context (Wood & Kroger, 2000).

In discourse analysis, the researcher interprets details of language materials and the context in which it is situated.

Discourse analysis aims to understand the functions of language (how language is used in real life) and how meaning is conveyed by language in different contexts. Researchers use discourse analysis to investigate social groups and how language is used to achieve specific communication goals.

Different methods of discourse analysis can be used depending on the aims and objectives of a study. However, the following steps provide a guideline on how to conduct discourse analysis.

- Define the Research Question : Develop a relevant research question to frame the analysis.

- Gather Data and Establish the Context : Collect research materials (e.g., interview transcripts, documents). Gather factual details and review the literature to construct a theory about the social and historical context of your study.

- Analyze the Content : Closely examine various components of the text, such as the vocabulary, sentences, paragraphs, and structure of the text. Identify patterns relevant to the research question to create codes, then group these into themes.

- Review the Results : Reflect on the findings to examine the function of the language, and the meaning and context of the discourse.

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis is a method used to identify, interpret, and report patterns in data, such as commonalities or contrasts.

Although the origin of thematic analysis can be traced back to the early twentieth century, understanding and clarity of thematic analysis is attributed to Braun and Clarke (2006).

Thematic analysis aims to develop themes (patterns of meaning) across a dataset to address a research question.

In thematic analysis, qualitative data is gathered using techniques such as interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires. Audio recordings are transcribed. The dataset is then explored and interpreted by a researcher to identify patterns.

This occurs through the rigorous process of data familiarisation, coding, theme development, and revision. These identified patterns provide a summary of the dataset and can be used to address a research question.

Themes are developed by exploring the implicit and explicit meanings within the data. Two different approaches are used to generate themes: inductive and deductive.

An inductive approach allows themes to emerge from the data. In contrast, a deductive approach uses existing theories or knowledge to apply preconceived ideas to the data.

Phases of Thematic Analysis

Braun and Clarke (2006) provide a guide of the six phases of thematic analysis. These phases can be applied flexibly to fit research questions and data.

Template analysis

Template analysis refers to a specific method of thematic analysis which uses hierarchical coding (Brooks et al., 2014).

Template analysis is used to analyze textual data, for example, interview transcripts or open-ended responses on a written questionnaire.

To conduct template analysis, a coding template must be developed (usually from a subset of the data) and subsequently revised and refined. This template represents the themes identified by researchers as important in the dataset.

Codes are ordered hierarchically within the template, with the highest-level codes demonstrating overarching themes in the data and lower-level codes representing constituent themes with a narrower focus.

A guideline for the main procedural steps for conducting template analysis is outlined below.

- Familiarization with the Data : Read (and reread) the dataset in full. Engage, reflect, and take notes on data that may be relevant to the research question.

- Preliminary Coding : Identify initial codes using guidance from the a priori codes, identified before the analysis as likely to be beneficial and relevant to the analysis.

- Organize Themes : Organize themes into meaningful clusters. Consider the relationships between the themes both within and between clusters.

- Produce an Initial Template : Develop an initial template. This may be based on a subset of the data.

- Apply and Develop the Template : Apply the initial template to further data and make any necessary modifications. Refinements of the template may include adding themes, removing themes, or changing the scope/title of themes.

- Finalize Template : Finalize the template, then apply it to the entire dataset.

Frame analysis

Frame analysis is a comparative form of thematic analysis which systematically analyzes data using a matrix output.

Ritchie and Spencer (1994) developed this set of techniques to analyze qualitative data in applied policy research. Frame analysis aims to generate theory from data.

Frame analysis encourages researchers to organize and manage their data using summarization.

This results in a flexible and unique matrix output, in which individual participants (or cases) are represented by rows and themes are represented by columns.

Each intersecting cell is used to summarize findings relating to the corresponding participant and theme.

Frame analysis has five distinct phases which are interrelated, forming a methodical and rigorous framework.

- Familiarization with the Data : Familiarize yourself with all the transcripts. Immerse yourself in the details of each transcript and start to note recurring themes.

- Develop a Theoretical Framework : Identify recurrent/ important themes and add them to a chart. Provide a framework/ structure for the analysis.

- Indexing : Apply the framework systematically to the entire study data.

- Summarize Data in Analytical Framework : Reduce the data into brief summaries of participants’ accounts.

- Mapping and Interpretation : Compare themes and subthemes and check against the original transcripts. Group the data into categories and provide an explanation for them.

Preventing Bias in Qualitative Research

To evaluate qualitative studies, the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) checklist for qualitative studies can be used to ensure all aspects of a study have been considered (CASP, 2018).

The quality of research can be enhanced and assessed using criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, co-coding, and member-checking.

Co-coding

Relying on only one researcher to interpret rich and complex data may risk key insights and alternative viewpoints being missed. Therefore, coding is often performed by multiple researchers.

A common strategy must be defined at the beginning of the coding process (Busetto et al., 2020). This includes establishing a useful coding list and finding a common definition of individual codes.

Transcripts are initially coded independently by researchers and then compared and consolidated to minimize error or bias and to bring confirmation of findings.

Member checking

Member checking (or respondent validation) involves checking back with participants to see if the research resonates with their experiences (Russell & Gregory, 2003).

Data can be returned to participants after data collection or when results are first available. For example, participants may be provided with their interview transcript and asked to verify whether this is a complete and accurate representation of their views.

Participants may then clarify or elaborate on their responses to ensure they align with their views (Shenton, 2004).

This feedback becomes part of data collection and ensures accurate descriptions/ interpretations of phenomena (Mays & Pope, 2000).

Reflexivity in qualitative research

Reflexivity typically involves examining your own judgments, practices, and belief systems during data collection and analysis. It aims to identify any personal beliefs which may affect the research.

Reflexivity is essential in qualitative research to ensure methodological transparency and complete reporting. This enables readers to understand how the interaction between the researcher and participant shapes the data.

Depending on the research question and population being researched, factors that need to be considered include the experience of the researcher, how the contact was established and maintained, age, gender, and ethnicity.

These details are important because, in qualitative research, the researcher is a dynamic part of the research process and actively influences the outcome of the research (Boeije, 2014).

Reflexivity Example

Who you are and your characteristics influence how you collect and analyze data. Here is an example of a reflexivity statement for research on smoking. I am a 30-year-old white female from a middle-class background. I live in the southwest of England and have been educated to master’s level. I have been involved in two research projects on oral health. I have never smoked, but I have witnessed how smoking can cause ill health from my volunteering in a smoking cessation clinic. My research aspirations are to help to develop interventions to help smokers quit.

Establishing Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research

Trustworthiness is a concept used to assess the quality and rigor of qualitative research. Four criteria are used to assess a study’s trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

Credibility in Qualitative Research

Credibility refers to how accurately the results represent the reality and viewpoints of the participants.

To establish credibility in research, participants’ views and the researcher’s representation of their views need to align (Tobin & Begley, 2004).

To increase the credibility of findings, researchers may use data source triangulation, investigator triangulation, peer debriefing, or member checking (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Transferability in Qualitative Research

Transferability refers to how generalizable the findings are: whether the findings may be applied to another context, setting, or group (Tobin & Begley, 2004).

Transferability can be enhanced by giving thorough and in-depth descriptions of the research setting, sample, and methods (Nowell et al., 2017).

Dependability in Qualitative Research

Dependability is the extent to which the study could be replicated under similar conditions and the findings would be consistent.

Researchers can establish dependability using methods such as audit trails so readers can see the research process is logical and traceable (Koch, 1994).

Confirmability in Qualitative Research

Confirmability is concerned with establishing that there is a clear link between the researcher’s interpretations/ findings and the data.

Researchers can achieve confirmability by demonstrating how conclusions and interpretations were arrived at (Nowell et al., 2017).

This enables readers to understand the reasoning behind the decisions made.

Audit Trails in Qualitative Research

An audit trail provides evidence of the decisions made by the researcher regarding theory, research design, and data collection, as well as the steps they have chosen to manage, analyze, and report data.

The researcher must provide a clear rationale to demonstrate how conclusions were reached in their study.

A clear description of the research path must be provided to enable readers to trace through the researcher’s logic (Halpren, 1983).

Researchers should maintain records of the raw data, field notes, transcripts, and a reflective journal in order to provide a clear audit trail.

Discovery of unexpected data

Open-ended questions in qualitative research mean the researcher can probe an interview topic and enable the participant to elaborate on responses in an unrestricted manner.

This allows unexpected data to emerge, which can lead to further research into that topic.

The exploratory nature of qualitative research helps generate hypotheses that can be tested quantitatively (Busetto et al., 2020).

Flexibility

Data collection and analysis can be modified and adapted to take the research in a different direction if new ideas or patterns emerge in the data.

This enables researchers to investigate new opportunities while firmly maintaining their research goals.

Naturalistic settings

The behaviors of participants are recorded in real-world settings. Studies that use real-world settings have high ecological validity since participants behave more authentically.

Limitations

Time-consuming .

Qualitative research results in large amounts of data which often need to be transcribed and analyzed manually.

Even when software is used, transcription can be inaccurate, and using software for analysis can result in many codes which need to be condensed into themes.

Subjectivity

The researcher has an integral role in collecting and interpreting qualitative data. Therefore, the conclusions reached are from their perspective and experience.

Consequently, interpretations of data from another researcher may vary greatly.

Limited generalizability

The aim of qualitative research is to provide a detailed, contextualized understanding of an aspect of the human experience from a relatively small sample size.

Despite rigorous analysis procedures, conclusions drawn cannot be generalized to the wider population since data may be biased or unrepresentative.

Therefore, results are only applicable to a small group of the population.

Extraneous variables

Qualitative research is often conducted in real-world settings. This may cause results to be unreliable since extraneous variables may affect the data, for example:

- Situational variables : different environmental conditions may influence participants’ behavior in a study. The random variation in factors (such as noise or lighting) may be difficult to control in real-world settings.

- Participant characteristics : this includes any characteristics that may influence how a participant answers/ behaves in a study. This may include a participant’s mood, gender, age, ethnicity, sexual identity, IQ, etc.

- Experimenter effect : experimenter effect refers to how a researcher’s unintentional influence can change the outcome of a study. This occurs when (i) their interactions with participants unintentionally change participants’ behaviors or (ii) due to errors in observation, interpretation, or analysis.

What sample size should qualitative research be?

The sample size for qualitative studies has been recommended to include a minimum of 12 participants to reach data saturation (Braun, 2013).

Are surveys qualitative or quantitative?

Surveys can be used to gather information from a sample qualitatively or quantitatively. Qualitative surveys use open-ended questions to gather detailed information from a large sample using free text responses.

The use of open-ended questions allows for unrestricted responses where participants use their own words, enabling the collection of more in-depth information than closed-ended questions.

In contrast, quantitative surveys consist of closed-ended questions with multiple-choice answer options. Quantitative surveys are ideal to gather a statistical representation of a population.

What are the ethical considerations of qualitative research?

Before conducting a study, you must think about any risks that could occur and take steps to prevent them. Participant Protection : Researchers must protect participants from physical and mental harm. This means you must not embarrass, frighten, offend, or harm participants. Transparency : Researchers are obligated to clearly communicate how they will collect, store, analyze, use, and share the data. Confidentiality : You need to consider how to maintain the confidentiality and anonymity of participants’ data.

What is triangulation in qualitative research?

Triangulation refers to the use of several approaches in a study to comprehensively understand phenomena. This method helps to increase the validity and credibility of research findings.

Types of triangulation include method triangulation (using multiple methods to gather data); investigator triangulation (multiple researchers for collecting/ analyzing data), theory triangulation (comparing several theoretical perspectives to explain a phenomenon), and data source triangulation (using data from various times, locations, and people; Carter et al., 2014).

Why is qualitative research important?

Qualitative research allows researchers to describe and explain the social world. The exploratory nature of qualitative research helps to generate hypotheses that can then be tested quantitatively.

In qualitative research, participants are able to express their thoughts, experiences, and feelings without constraint.

Additionally, researchers are able to follow up on participants’ answers in real-time, generating valuable discussion around a topic. This enables researchers to gain a nuanced understanding of phenomena which is difficult to attain using quantitative methods.

What is coding data in qualitative research?

Coding data is a qualitative data analysis strategy in which a section of text is assigned with a label that describes its content.

These labels may be words or phrases which represent important (and recurring) patterns in the data.

This process enables researchers to identify related content across the dataset. Codes can then be used to group similar types of data to generate themes.

What is the difference between qualitative and quantitative research?

Qualitative research involves the collection and analysis of non-numerical data in order to understand experiences and meanings from the participant’s perspective.

This can provide rich, in-depth insights on complicated phenomena. Qualitative data may be collected using interviews, focus groups, or observations.

In contrast, quantitative research involves the collection and analysis of numerical data to measure the frequency, magnitude, or relationships of variables. This can provide objective and reliable evidence that can be generalized to the wider population.

Quantitative data may be collected using closed-ended questionnaires or experiments.

What is trustworthiness in qualitative research?

Trustworthiness is a concept used to assess the quality and rigor of qualitative research. Four criteria are used to assess a study’s trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

Credibility refers to how accurately the results represent the reality and viewpoints of the participants. Transferability refers to whether the findings may be applied to another context, setting, or group.

Dependability is the extent to which the findings are consistent and reliable. Confirmability refers to the objectivity of findings (not influenced by the bias or assumptions of researchers).

What is data saturation in qualitative research?

Data saturation is a methodological principle used to guide the sample size of a qualitative research study.

Data saturation is proposed as a necessary methodological component in qualitative research (Saunders et al., 2018) as it is a vital criterion for discontinuing data collection and/or analysis.

The intention of data saturation is to find “no new data, no new themes, no new coding, and ability to replicate the study” (Guest et al., 2006). Therefore, enough data has been gathered to make conclusions.

Why is sampling in qualitative research important?

In quantitative research, large sample sizes are used to provide statistically significant quantitative estimates.

This is because quantitative research aims to provide generalizable conclusions that represent populations.

However, the aim of sampling in qualitative research is to gather data that will help the researcher understand the depth, complexity, variation, or context of a phenomenon. The small sample sizes in qualitative studies support the depth of case-oriented analysis.

Boeije, H. (2014). Analysis in qualitative research. Sage.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology , 3 (2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brooks, J., McCluskey, S., Turley, E., & King, N. (2014). The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qualitative Research in Psychology , 12 (2), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

Busetto, L., Wick, W., & Gumbinger, C. (2020). How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurological research and practice , 2 (1), 14-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology nursing forum , 41 (5), 545–547. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP Checklist: 10 questions to help you make sense of a Qualitative research. https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf Accessed: March 15 2023

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Successful Qualitative Research , 1-400.

Denny, E., & Weckesser, A. (2022). How to do qualitative research?: Qualitative research methods. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology , 129 (7), 1166-1167. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17150

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). The discovery of grounded theory. The Discovery of Grounded Theory , 1–18. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203793206-1

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18 (1), 59-82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903

Halpren, E. S. (1983). Auditing naturalistic inquiries: The development and application of a model (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Indiana University, Bloomington.

Hammarberg, K., Kirkman, M., & de Lacey, S. (2016). Qualitative research methods: When to use them and how to judge them. Human Reproduction , 31 (3), 498–501. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev334

Koch, T. (1994). Establishing rigour in qualitative research: The decision trail. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19, 976–986. doi:10.1111/ j.1365-2648.1994.tb01177.x

Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320(7226), 50–52.

Minichiello, V. (1990). In-Depth Interviewing: Researching People. Longman Cheshire.

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16 (1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

Petty, N. J., Thomson, O. P., & Stew, G. (2012). Ready for a paradigm shift? part 2: Introducing qualitative research methodologies and methods. Manual Therapy , 17 (5), 378–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2012.03.004

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. London: Sage

Reeves, S., Kuper, A., & Hodges, B. D. (2008). Qualitative research methodologies: Ethnography. BMJ , 337 (aug07 3). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1020

Russell, C. K., & Gregory, D. M. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Evidence Based Nursing, 6 (2), 36–40.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & quantity , 52 (4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

Scarduzio, J. A. (2017). Emic approach to qualitative research. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, 1–2 . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0082

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice / Margrit Schreier.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 , 63–75.

Starks, H., & Trinidad, S. B. (2007). Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative health research , 17 (10), 1372–1380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307307031

Tenny, S., Brannan, J. M., & Brannan, G. D. (2022). Qualitative Study. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

Tobin, G. A., & Begley, C. M. (2004). Methodological rigour within a qualitative framework. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48, 388–396. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03207.x

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & health sciences , 15 (3), 398-405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

Wood L. A., Kroger R. O. (2000). Doing discourse analysis: Methods for studying action in talk and text. Sage.

Yilmaz, K. (2013). Comparison of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Traditions: epistemological, theoretical, and methodological differences. European journal of education , 48 (2), 311-325. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12014

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

Chapter 1. Introduction

“Science is in danger, and for that reason it is becoming dangerous” -Pierre Bourdieu, Science of Science and Reflexivity

Why an Open Access Textbook on Qualitative Research Methods?

I have been teaching qualitative research methods to both undergraduates and graduate students for many years. Although there are some excellent textbooks out there, they are often costly, and none of them, to my mind, properly introduces qualitative research methods to the beginning student (whether undergraduate or graduate student). In contrast, this open-access textbook is designed as a (free) true introduction to the subject, with helpful, practical pointers on how to conduct research and how to access more advanced instruction.

Textbooks are typically arranged in one of two ways: (1) by technique (each chapter covers one method used in qualitative research); or (2) by process (chapters advance from research design through publication). But both of these approaches are necessary for the beginner student. This textbook will have sections dedicated to the process as well as the techniques of qualitative research. This is a true “comprehensive” book for the beginning student. In addition to covering techniques of data collection and data analysis, it provides a road map of how to get started and how to keep going and where to go for advanced instruction. It covers aspects of research design and research communication as well as methods employed. Along the way, it includes examples from many different disciplines in the social sciences.

The primary goal has been to create a useful, accessible, engaging textbook for use across many disciplines. And, let’s face it. Textbooks can be boring. I hope readers find this to be a little different. I have tried to write in a practical and forthright manner, with many lively examples and references to good and intellectually creative qualitative research. Woven throughout the text are short textual asides (in colored textboxes) by professional (academic) qualitative researchers in various disciplines. These short accounts by practitioners should help inspire students. So, let’s begin!

What is Research?

When we use the word research , what exactly do we mean by that? This is one of those words that everyone thinks they understand, but it is worth beginning this textbook with a short explanation. We use the term to refer to “empirical research,” which is actually a historically specific approach to understanding the world around us. Think about how you know things about the world. [1] You might know your mother loves you because she’s told you she does. Or because that is what “mothers” do by tradition. Or you might know because you’ve looked for evidence that she does, like taking care of you when you are sick or reading to you in bed or working two jobs so you can have the things you need to do OK in life. Maybe it seems churlish to look for evidence; you just take it “on faith” that you are loved.

Only one of the above comes close to what we mean by research. Empirical research is research (investigation) based on evidence. Conclusions can then be drawn from observable data. This observable data can also be “tested” or checked. If the data cannot be tested, that is a good indication that we are not doing research. Note that we can never “prove” conclusively, through observable data, that our mothers love us. We might have some “disconfirming evidence” (that time she didn’t show up to your graduation, for example) that could push you to question an original hypothesis , but no amount of “confirming evidence” will ever allow us to say with 100% certainty, “my mother loves me.” Faith and tradition and authority work differently. Our knowledge can be 100% certain using each of those alternative methods of knowledge, but our certainty in those cases will not be based on facts or evidence.

For many periods of history, those in power have been nervous about “science” because it uses evidence and facts as the primary source of understanding the world, and facts can be at odds with what power or authority or tradition want you to believe. That is why I say that scientific empirical research is a historically specific approach to understand the world. You are in college or university now partly to learn how to engage in this historically specific approach.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe, there was a newfound respect for empirical research, some of which was seriously challenging to the established church. Using observations and testing them, scientists found that the earth was not at the center of the universe, for example, but rather that it was but one planet of many which circled the sun. [2] For the next two centuries, the science of astronomy, physics, biology, and chemistry emerged and became disciplines taught in universities. All used the scientific method of observation and testing to advance knowledge. Knowledge about people , however, and social institutions, however, was still left to faith, tradition, and authority. Historians and philosophers and poets wrote about the human condition, but none of them used research to do so. [3]

It was not until the nineteenth century that “social science” really emerged, using the scientific method (empirical observation) to understand people and social institutions. New fields of sociology, economics, political science, and anthropology emerged. The first sociologists, people like Auguste Comte and Karl Marx, sought specifically to apply the scientific method of research to understand society, Engels famously claiming that Marx had done for the social world what Darwin did for the natural world, tracings its laws of development. Today we tend to take for granted the naturalness of science here, but it is actually a pretty recent and radical development.

To return to the question, “does your mother love you?” Well, this is actually not really how a researcher would frame the question, as it is too specific to your case. It doesn’t tell us much about the world at large, even if it does tell us something about you and your relationship with your mother. A social science researcher might ask, “do mothers love their children?” Or maybe they would be more interested in how this loving relationship might change over time (e.g., “do mothers love their children more now than they did in the 18th century when so many children died before reaching adulthood?”) or perhaps they might be interested in measuring quality of love across cultures or time periods, or even establishing “what love looks like” using the mother/child relationship as a site of exploration. All of these make good research questions because we can use observable data to answer them.

What is Qualitative Research?

“All we know is how to learn. How to study, how to listen, how to talk, how to tell. If we don’t tell the world, we don’t know the world. We’re lost in it, we die.” -Ursula LeGuin, The Telling

At its simplest, qualitative research is research about the social world that does not use numbers in its analyses. All those who fear statistics can breathe a sigh of relief – there are no mathematical formulae or regression models in this book! But this definition is less about what qualitative research can be and more about what it is not. To be honest, any simple statement will fail to capture the power and depth of qualitative research. One way of contrasting qualitative research to quantitative research is to note that the focus of qualitative research is less about explaining and predicting relationships between variables and more about understanding the social world. To use our mother love example, the question about “what love looks like” is a good question for the qualitative researcher while all questions measuring love or comparing incidences of love (both of which require measurement) are good questions for quantitative researchers. Patton writes,

Qualitative data describe. They take us, as readers, into the time and place of the observation so that we know what it was like to have been there. They capture and communicate someone else’s experience of the world in his or her own words. Qualitative data tell a story. ( Patton 2002:47 )

Qualitative researchers are asking different questions about the world than their quantitative colleagues. Even when researchers are employed in “mixed methods” research ( both quantitative and qualitative), they are using different methods to address different questions of the study. I do a lot of research about first-generation and working-college college students. Where a quantitative researcher might ask, how many first-generation college students graduate from college within four years? Or does first-generation college status predict high student debt loads? A qualitative researcher might ask, how does the college experience differ for first-generation college students? What is it like to carry a lot of debt, and how does this impact the ability to complete college on time? Both sets of questions are important, but they can only be answered using specific tools tailored to those questions. For the former, you need large numbers to make adequate comparisons. For the latter, you need to talk to people, find out what they are thinking and feeling, and try to inhabit their shoes for a little while so you can make sense of their experiences and beliefs.

Examples of Qualitative Research

You have probably seen examples of qualitative research before, but you might not have paid particular attention to how they were produced or realized that the accounts you were reading were the result of hours, months, even years of research “in the field.” A good qualitative researcher will present the product of their hours of work in such a way that it seems natural, even obvious, to the reader. Because we are trying to convey what it is like answers, qualitative research is often presented as stories – stories about how people live their lives, go to work, raise their children, interact with one another. In some ways, this can seem like reading particularly insightful novels. But, unlike novels, there are very specific rules and guidelines that qualitative researchers follow to ensure that the “story” they are telling is accurate , a truthful rendition of what life is like for the people being studied. Most of this textbook will be spent conveying those rules and guidelines. Let’s take a look, first, however, at three examples of what the end product looks like. I have chosen these three examples to showcase very different approaches to qualitative research, and I will return to these five examples throughout the book. They were all published as whole books (not chapters or articles), and they are worth the long read, if you have the time. I will also provide some information on how these books came to be and the length of time it takes to get them into book version. It is important you know about this process, and the rest of this textbook will help explain why it takes so long to conduct good qualitative research!

Example 1 : The End Game (ethnography + interviews)

Corey Abramson is a sociologist who teaches at the University of Arizona. In 2015 he published The End Game: How Inequality Shapes our Final Years ( 2015 ). This book was based on the research he did for his dissertation at the University of California-Berkeley in 2012. Actually, the dissertation was completed in 2012 but the work that was produced that took several years. The dissertation was entitled, “This is How We Live, This is How We Die: Social Stratification, Aging, and Health in Urban America” ( 2012 ). You can see how the book version, which was written for a more general audience, has a more engaging sound to it, but that the dissertation version, which is what academic faculty read and evaluate, has a more descriptive title. You can read the title and know that this is a study about aging and health and that the focus is going to be inequality and that the context (place) is going to be “urban America.” It’s a study about “how” people do something – in this case, how they deal with aging and death. This is the very first sentence of the dissertation, “From our first breath in the hospital to the day we die, we live in a society characterized by unequal opportunities for maintaining health and taking care of ourselves when ill. These disparities reflect persistent racial, socio-economic, and gender-based inequalities and contribute to their persistence over time” ( 1 ). What follows is a truthful account of how that is so.

Cory Abramson spent three years conducting his research in four different urban neighborhoods. We call the type of research he conducted “comparative ethnographic” because he designed his study to compare groups of seniors as they went about their everyday business. It’s comparative because he is comparing different groups (based on race, class, gender) and ethnographic because he is studying the culture/way of life of a group. [4] He had an educated guess, rooted in what previous research had shown and what social theory would suggest, that people’s experiences of aging differ by race, class, and gender. So, he set up a research design that would allow him to observe differences. He chose two primarily middle-class (one was racially diverse and the other was predominantly White) and two primarily poor neighborhoods (one was racially diverse and the other was predominantly African American). He hung out in senior centers and other places seniors congregated, watched them as they took the bus to get prescriptions filled, sat in doctor’s offices with them, and listened to their conversations with each other. He also conducted more formal conversations, what we call in-depth interviews, with sixty seniors from each of the four neighborhoods. As with a lot of fieldwork , as he got closer to the people involved, he both expanded and deepened his reach –

By the end of the project, I expanded my pool of general observations to include various settings frequented by seniors: apartment building common rooms, doctors’ offices, emergency rooms, pharmacies, senior centers, bars, parks, corner stores, shopping centers, pool halls, hair salons, coffee shops, and discount stores. Over the course of the three years of fieldwork, I observed hundreds of elders, and developed close relationships with a number of them. ( 2012:10 )

When Abramson rewrote the dissertation for a general audience and published his book in 2015, it got a lot of attention. It is a beautifully written book and it provided insight into a common human experience that we surprisingly know very little about. It won the Outstanding Publication Award by the American Sociological Association Section on Aging and the Life Course and was featured in the New York Times . The book was about aging, and specifically how inequality shapes the aging process, but it was also about much more than that. It helped show how inequality affects people’s everyday lives. For example, by observing the difficulties the poor had in setting up appointments and getting to them using public transportation and then being made to wait to see a doctor, sometimes in standing-room-only situations, when they are unwell, and then being treated dismissively by hospital staff, Abramson allowed readers to feel the material reality of being poor in the US. Comparing these examples with seniors with adequate supplemental insurance who have the resources to hire car services or have others assist them in arranging care when they need it, jolts the reader to understand and appreciate the difference money makes in the lives and circumstances of us all, and in a way that is different than simply reading a statistic (“80% of the poor do not keep regular doctor’s appointments”) does. Qualitative research can reach into spaces and places that often go unexamined and then reports back to the rest of us what it is like in those spaces and places.

Example 2: Racing for Innocence (Interviews + Content Analysis + Fictional Stories)

Jennifer Pierce is a Professor of American Studies at the University of Minnesota. Trained as a sociologist, she has written a number of books about gender, race, and power. Her very first book, Gender Trials: Emotional Lives in Contemporary Law Firms, published in 1995, is a brilliant look at gender dynamics within two law firms. Pierce was a participant observer, working as a paralegal, and she observed how female lawyers and female paralegals struggled to obtain parity with their male colleagues.

Fifteen years later, she reexamined the context of the law firm to include an examination of racial dynamics, particularly how elite white men working in these spaces created and maintained a culture that made it difficult for both female attorneys and attorneys of color to thrive. Her book, Racing for Innocence: Whiteness, Gender, and the Backlash Against Affirmative Action , published in 2012, is an interesting and creative blending of interviews with attorneys, content analyses of popular films during this period, and fictional accounts of racial discrimination and sexual harassment. The law firm she chose to study had come under an affirmative action order and was in the process of implementing equitable policies and programs. She wanted to understand how recipients of white privilege (the elite white male attorneys) come to deny the role they play in reproducing inequality. Through interviews with attorneys who were present both before and during the affirmative action order, she creates a historical record of the “bad behavior” that necessitated new policies and procedures, but also, and more importantly , probed the participants ’ understanding of this behavior. It should come as no surprise that most (but not all) of the white male attorneys saw little need for change, and that almost everyone else had accounts that were different if not sometimes downright harrowing.

I’ve used Pierce’s book in my qualitative research methods courses as an example of an interesting blend of techniques and presentation styles. My students often have a very difficult time with the fictional accounts she includes. But they serve an important communicative purpose here. They are her attempts at presenting “both sides” to an objective reality – something happens (Pierce writes this something so it is very clear what it is), and the two participants to the thing that happened have very different understandings of what this means. By including these stories, Pierce presents one of her key findings – people remember things differently and these different memories tend to support their own ideological positions. I wonder what Pierce would have written had she studied the murder of George Floyd or the storming of the US Capitol on January 6 or any number of other historic events whose observers and participants record very different happenings.

This is not to say that qualitative researchers write fictional accounts. In fact, the use of fiction in our work remains controversial. When used, it must be clearly identified as a presentation device, as Pierce did. I include Racing for Innocence here as an example of the multiple uses of methods and techniques and the way that these work together to produce better understandings by us, the readers, of what Pierce studied. We readers come away with a better grasp of how and why advantaged people understate their own involvement in situations and structures that advantage them. This is normal human behavior , in other words. This case may have been about elite white men in law firms, but the general insights here can be transposed to other settings. Indeed, Pierce argues that more research needs to be done about the role elites play in the reproduction of inequality in the workplace in general.

Example 3: Amplified Advantage (Mixed Methods: Survey Interviews + Focus Groups + Archives)

The final example comes from my own work with college students, particularly the ways in which class background affects the experience of college and outcomes for graduates. I include it here as an example of mixed methods, and for the use of supplementary archival research. I’ve done a lot of research over the years on first-generation, low-income, and working-class college students. I am curious (and skeptical) about the possibility of social mobility today, particularly with the rising cost of college and growing inequality in general. As one of the few people in my family to go to college, I didn’t grow up with a lot of examples of what college was like or how to make the most of it. And when I entered graduate school, I realized with dismay that there were very few people like me there. I worried about becoming too different from my family and friends back home. And I wasn’t at all sure that I would ever be able to pay back the huge load of debt I was taking on. And so I wrote my dissertation and first two books about working-class college students. These books focused on experiences in college and the difficulties of navigating between family and school ( Hurst 2010a, 2012 ). But even after all that research, I kept coming back to wondering if working-class students who made it through college had an equal chance at finding good jobs and happy lives,

What happens to students after college? Do working-class students fare as well as their peers? I knew from my own experience that barriers continued through graduate school and beyond, and that my debtload was higher than that of my peers, constraining some of the choices I made when I graduated. To answer these questions, I designed a study of students attending small liberal arts colleges, the type of college that tried to equalize the experience of students by requiring all students to live on campus and offering small classes with lots of interaction with faculty. These private colleges tend to have more money and resources so they can provide financial aid to low-income students. They also attract some very wealthy students. Because they enroll students across the class spectrum, I would be able to draw comparisons. I ended up spending about four years collecting data, both a survey of more than 2000 students (which formed the basis for quantitative analyses) and qualitative data collection (interviews, focus groups, archival research, and participant observation). This is what we call a “mixed methods” approach because we use both quantitative and qualitative data. The survey gave me a large enough number of students that I could make comparisons of the how many kind, and to be able to say with some authority that there were in fact significant differences in experience and outcome by class (e.g., wealthier students earned more money and had little debt; working-class students often found jobs that were not in their chosen careers and were very affected by debt, upper-middle-class students were more likely to go to graduate school). But the survey analyses could not explain why these differences existed. For that, I needed to talk to people and ask them about their motivations and aspirations. I needed to understand their perceptions of the world, and it is very hard to do this through a survey.

By interviewing students and recent graduates, I was able to discern particular patterns and pathways through college and beyond. Specifically, I identified three versions of gameplay. Upper-middle-class students, whose parents were themselves professionals (academics, lawyers, managers of non-profits), saw college as the first stage of their education and took classes and declared majors that would prepare them for graduate school. They also spent a lot of time building their resumes, taking advantage of opportunities to help professors with their research, or study abroad. This helped them gain admission to highly-ranked graduate schools and interesting jobs in the public sector. In contrast, upper-class students, whose parents were wealthy and more likely to be engaged in business (as CEOs or other high-level directors), prioritized building social capital. They did this by joining fraternities and sororities and playing club sports. This helped them when they graduated as they called on friends and parents of friends to find them well-paying jobs. Finally, low-income, first-generation, and working-class students were often adrift. They took the classes that were recommended to them but without the knowledge of how to connect them to life beyond college. They spent time working and studying rather than partying or building their resumes. All three sets of students thought they were “doing college” the right way, the way that one was supposed to do college. But these three versions of gameplay led to distinct outcomes that advantaged some students over others. I titled my work “Amplified Advantage” to highlight this process.

These three examples, Cory Abramson’s The End Game , Jennifer Peirce’s Racing for Innocence, and my own Amplified Advantage, demonstrate the range of approaches and tools available to the qualitative researcher. They also help explain why qualitative research is so important. Numbers can tell us some things about the world, but they cannot get at the hearts and minds, motivations and beliefs of the people who make up the social worlds we inhabit. For that, we need tools that allow us to listen and make sense of what people tell us and show us. That is what good qualitative research offers us.

How Is This Book Organized?

This textbook is organized as a comprehensive introduction to the use of qualitative research methods. The first half covers general topics (e.g., approaches to qualitative research, ethics) and research design (necessary steps for building a successful qualitative research study). The second half reviews various data collection and data analysis techniques. Of course, building a successful qualitative research study requires some knowledge of data collection and data analysis so the chapters in the first half and the chapters in the second half should be read in conversation with each other. That said, each chapter can be read on its own for assistance with a particular narrow topic. In addition to the chapters, a helpful glossary can be found in the back of the book. Rummage around in the text as needed.

Chapter Descriptions

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the Research Design Process. How does one begin a study? What is an appropriate research question? How is the study to be done – with what methods ? Involving what people and sites? Although qualitative research studies can and often do change and develop over the course of data collection, it is important to have a good idea of what the aims and goals of your study are at the outset and a good plan of how to achieve those aims and goals. Chapter 2 provides a road map of the process.

Chapter 3 describes and explains various ways of knowing the (social) world. What is it possible for us to know about how other people think or why they behave the way they do? What does it mean to say something is a “fact” or that it is “well-known” and understood? Qualitative researchers are particularly interested in these questions because of the types of research questions we are interested in answering (the how questions rather than the how many questions of quantitative research). Qualitative researchers have adopted various epistemological approaches. Chapter 3 will explore these approaches, highlighting interpretivist approaches that acknowledge the subjective aspect of reality – in other words, reality and knowledge are not objective but rather influenced by (interpreted through) people.

Chapter 4 focuses on the practical matter of developing a research question and finding the right approach to data collection. In any given study (think of Cory Abramson’s study of aging, for example), there may be years of collected data, thousands of observations , hundreds of pages of notes to read and review and make sense of. If all you had was a general interest area (“aging”), it would be very difficult, nearly impossible, to make sense of all of that data. The research question provides a helpful lens to refine and clarify (and simplify) everything you find and collect. For that reason, it is important to pull out that lens (articulate the research question) before you get started. In the case of the aging study, Cory Abramson was interested in how inequalities affected understandings and responses to aging. It is for this reason he designed a study that would allow him to compare different groups of seniors (some middle-class, some poor). Inevitably, he saw much more in the three years in the field than what made it into his book (or dissertation), but he was able to narrow down the complexity of the social world to provide us with this rich account linked to the original research question. Developing a good research question is thus crucial to effective design and a successful outcome. Chapter 4 will provide pointers on how to do this. Chapter 4 also provides an overview of general approaches taken to doing qualitative research and various “traditions of inquiry.”

Chapter 5 explores sampling . After you have developed a research question and have a general idea of how you will collect data (Observations? Interviews?), how do you go about actually finding people and sites to study? Although there is no “correct number” of people to interview , the sample should follow the research question and research design. Unlike quantitative research, qualitative research involves nonprobability sampling. Chapter 5 explains why this is so and what qualities instead make a good sample for qualitative research.

Chapter 6 addresses the importance of reflexivity in qualitative research. Related to epistemological issues of how we know anything about the social world, qualitative researchers understand that we the researchers can never be truly neutral or outside the study we are conducting. As observers, we see things that make sense to us and may entirely miss what is either too obvious to note or too different to comprehend. As interviewers, as much as we would like to ask questions neutrally and remain in the background, interviews are a form of conversation, and the persons we interview are responding to us . Therefore, it is important to reflect upon our social positions and the knowledges and expectations we bring to our work and to work through any blind spots that we may have. Chapter 6 provides some examples of reflexivity in practice and exercises for thinking through one’s own biases.

Chapter 7 is a very important chapter and should not be overlooked. As a practical matter, it should also be read closely with chapters 6 and 8. Because qualitative researchers deal with people and the social world, it is imperative they develop and adhere to a strong ethical code for conducting research in a way that does not harm. There are legal requirements and guidelines for doing so (see chapter 8), but these requirements should not be considered synonymous with the ethical code required of us. Each researcher must constantly interrogate every aspect of their research, from research question to design to sample through analysis and presentation, to ensure that a minimum of harm (ideally, zero harm) is caused. Because each research project is unique, the standards of care for each study are unique. Part of being a professional researcher is carrying this code in one’s heart, being constantly attentive to what is required under particular circumstances. Chapter 7 provides various research scenarios and asks readers to weigh in on the suitability and appropriateness of the research. If done in a class setting, it will become obvious fairly quickly that there are often no absolutely correct answers, as different people find different aspects of the scenarios of greatest importance. Minimizing the harm in one area may require possible harm in another. Being attentive to all the ethical aspects of one’s research and making the best judgments one can, clearly and consciously, is an integral part of being a good researcher.

Chapter 8 , best to be read in conjunction with chapter 7, explains the role and importance of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) . Under federal guidelines, an IRB is an appropriately constituted group that has been formally designated to review and monitor research involving human subjects . Every institution that receives funding from the federal government has an IRB. IRBs have the authority to approve, require modifications to (to secure approval), or disapprove research. This group review serves an important role in the protection of the rights and welfare of human research subjects. Chapter 8 reviews the history of IRBs and the work they do but also argues that IRBs’ review of qualitative research is often both over-inclusive and under-inclusive. Some aspects of qualitative research are not well understood by IRBs, given that they were developed to prevent abuses in biomedical research. Thus, it is important not to rely on IRBs to identify all the potential ethical issues that emerge in our research (see chapter 7).

Chapter 9 provides help for getting started on formulating a research question based on gaps in the pre-existing literature. Research is conducted as part of a community, even if particular studies are done by single individuals (or small teams). What any of us finds and reports back becomes part of a much larger body of knowledge. Thus, it is important that we look at the larger body of knowledge before we actually start our bit to see how we can best contribute. When I first began interviewing working-class college students, there was only one other similar study I could find, and it hadn’t been published (it was a dissertation of students from poor backgrounds). But there had been a lot published by professors who had grown up working class and made it through college despite the odds. These accounts by “working-class academics” became an important inspiration for my study and helped me frame the questions I asked the students I interviewed. Chapter 9 will provide some pointers on how to search for relevant literature and how to use this to refine your research question.

Chapter 10 serves as a bridge between the two parts of the textbook, by introducing techniques of data collection. Qualitative research is often characterized by the form of data collection – for example, an ethnographic study is one that employs primarily observational data collection for the purpose of documenting and presenting a particular culture or ethnos. Techniques can be effectively combined, depending on the research question and the aims and goals of the study. Chapter 10 provides a general overview of all the various techniques and how they can be combined.

The second part of the textbook moves into the doing part of qualitative research once the research question has been articulated and the study designed. Chapters 11 through 17 cover various data collection techniques and approaches. Chapters 18 and 19 provide a very simple overview of basic data analysis. Chapter 20 covers communication of the data to various audiences, and in various formats.

Chapter 11 begins our overview of data collection techniques with a focus on interviewing , the true heart of qualitative research. This technique can serve as the primary and exclusive form of data collection, or it can be used to supplement other forms (observation, archival). An interview is distinct from a survey, where questions are asked in a specific order and often with a range of predetermined responses available. Interviews can be conversational and unstructured or, more conventionally, semistructured , where a general set of interview questions “guides” the conversation. Chapter 11 covers the basics of interviews: how to create interview guides, how many people to interview, where to conduct the interview, what to watch out for (how to prepare against things going wrong), and how to get the most out of your interviews.

Chapter 12 covers an important variant of interviewing, the focus group. Focus groups are semistructured interviews with a group of people moderated by a facilitator (the researcher or researcher’s assistant). Focus groups explicitly use group interaction to assist in the data collection. They are best used to collect data on a specific topic that is non-personal and shared among the group. For example, asking a group of college students about a common experience such as taking classes by remote delivery during the pandemic year of 2020. Chapter 12 covers the basics of focus groups: when to use them, how to create interview guides for them, and how to run them effectively.

Chapter 13 moves away from interviewing to the second major form of data collection unique to qualitative researchers – observation . Qualitative research that employs observation can best be understood as falling on a continuum of “fly on the wall” observation (e.g., observing how strangers interact in a doctor’s waiting room) to “participant” observation, where the researcher is also an active participant of the activity being observed. For example, an activist in the Black Lives Matter movement might want to study the movement, using her inside position to gain access to observe key meetings and interactions. Chapter 13 covers the basics of participant observation studies: advantages and disadvantages, gaining access, ethical concerns related to insider/outsider status and entanglement, and recording techniques.

Chapter 14 takes a closer look at “deep ethnography” – immersion in the field of a particularly long duration for the purpose of gaining a deeper understanding and appreciation of a particular culture or social world. Clifford Geertz called this “deep hanging out.” Whereas participant observation is often combined with semistructured interview techniques, deep ethnography’s commitment to “living the life” or experiencing the situation as it really is demands more conversational and natural interactions with people. These interactions and conversations may take place over months or even years. As can be expected, there are some costs to this technique, as well as some very large rewards when done competently. Chapter 14 provides some examples of deep ethnographies that will inspire some beginning researchers and intimidate others.

Chapter 15 moves in the opposite direction of deep ethnography, a technique that is the least positivist of all those discussed here, to mixed methods , a set of techniques that is arguably the most positivist . A mixed methods approach combines both qualitative data collection and quantitative data collection, commonly by combining a survey that is analyzed statistically (e.g., cross-tabs or regression analyses of large number probability samples) with semi-structured interviews. Although it is somewhat unconventional to discuss mixed methods in textbooks on qualitative research, I think it is important to recognize this often-employed approach here. There are several advantages and some disadvantages to taking this route. Chapter 16 will describe those advantages and disadvantages and provide some particular guidance on how to design a mixed methods study for maximum effectiveness.

Chapter 16 covers data collection that does not involve live human subjects at all – archival and historical research (chapter 17 will also cover data that does not involve interacting with human subjects). Sometimes people are unavailable to us, either because they do not wish to be interviewed or observed (as is the case with many “elites”) or because they are too far away, in both place and time. Fortunately, humans leave many traces and we can often answer questions we have by examining those traces. Special collections and archives can be goldmines for social science research. This chapter will explain how to access these places, for what purposes, and how to begin to make sense of what you find.

Chapter 17 covers another data collection area that does not involve face-to-face interaction with humans: content analysis . Although content analysis may be understood more properly as a data analysis technique, the term is often used for the entire approach, which will be the case here. Content analysis involves interpreting meaning from a body of text. This body of text might be something found in historical records (see chapter 16) or something collected by the researcher, as in the case of comment posts on a popular blog post. I once used the stories told by student loan debtors on the website studentloanjustice.org as the content I analyzed. Content analysis is particularly useful when attempting to define and understand prevalent stories or communication about a topic of interest. In other words, when we are less interested in what particular people (our defined sample) are doing or believing and more interested in what general narratives exist about a particular topic or issue. This chapter will explore different approaches to content analysis and provide helpful tips on how to collect data, how to turn that data into codes for analysis, and how to go about presenting what is found through analysis.

Where chapter 17 has pushed us towards data analysis, chapters 18 and 19 are all about what to do with the data collected, whether that data be in the form of interview transcripts or fieldnotes from observations. Chapter 18 introduces the basics of coding , the iterative process of assigning meaning to the data in order to both simplify and identify patterns. What is a code and how does it work? What are the different ways of coding data, and when should you use them? What is a codebook, and why do you need one? What does the process of data analysis look like?